Intensive English Programs (IEPs) in the United States provide English language instruction to international students and visitors. Traditionally, this has been primarily through Academic English programs, offering preparation for study at U.S. universities, but also through short-term General English or Business English programs (for executives) and, in recent years, English summer camps for teens.

Intensive English Programs first appeared on the scene in the U.S. in the 1960s, along with the establishment of the private-sector language school chain, ELS, now a part of the Berlitz Corporation.

Over the years, Intensive English Programs have seen significant growth. This growth has manifested itself not just in the demand for language study but also, perhaps most notably, in the proliferation of schools. According to the Department of Homeland Security database, there are currently 2,595 SEVP (Student and Exchange Visitor Program) registered schools in the U.S. approved to accept international students studying language under the F1 visa. Of these “registered schools” it is estimated that approximately 500 to 600 operate as formal IEPs.

The last 15 years have also seen a more mature market characterized by consolidation in the private sector and the expansion of chain schools. These schools are typically hosted on university campuses or run as “city centers” in top tourist destinations. In many cases, this growth has been funded by private equity firms looking to invest in the expansion of international education and global student mobility.

The proliferation of language schools offering Intensive English Programs has comprised four distinct models:

- Independent language schools – Often privately-owned small businesses, most commonly located in urban city centers.

- University & college-administered IEPs – Faculty and administrative staff are university employees; often run by extension or international offices.

- Private sector/university partnerships – Privately-owned centers, usually chain schools, hosted on university campuses; often paying universities rent or a tuition royalty.

- University pathway programs – Privately-owned companies that sometimes form a joint venture with universities to offer intensive English but also academic courses, with universities bestowing international students’ freshman year tuition revenue in exchange for international student recruitment.

For all this expansion – even prior to the current and well-documented downturn in student numbers, which began in 2015 – the growth of Intensive English Programs (supply) has more than kept pace with the growth in the number of students (demand). With regard to demand, this is true of international students pursuing degrees at U.S. universities that require intensive English training, but also of short-term language students that typically frequent privately-owned language centers.

A History of Short-Term Volatility

Overall growth notwithstanding, the sector has historically been characterized by large, sudden fluctuations of students, often accompanying geopolitical and economic events. The most cited first crash in student enrollments occurred with the fall of the Shah of Iran in 1979, at a time when Iran was the number-one source of students in the United States, numbering 51,310 – more than any other country.

The sector also suffered significant short-term decreases in enrollment as a result of the SARS epidemic, the September 11th terrorist attacks, the Asian recession of 1997, and fluctuations in the strength of the dollar vis-à-vis some developing economy currencies, including those of Argentina and Brazil in the 1990s.

Most notably, IEPs were the first to be impacted by the curtailment of the King Abdullah Scholarship Program (KASP) and Brazilian Science without Borders (SwB) program, both of which funneled students into degree programs. This early impact earned IEPs the moniker “canaries in the coal mine.”

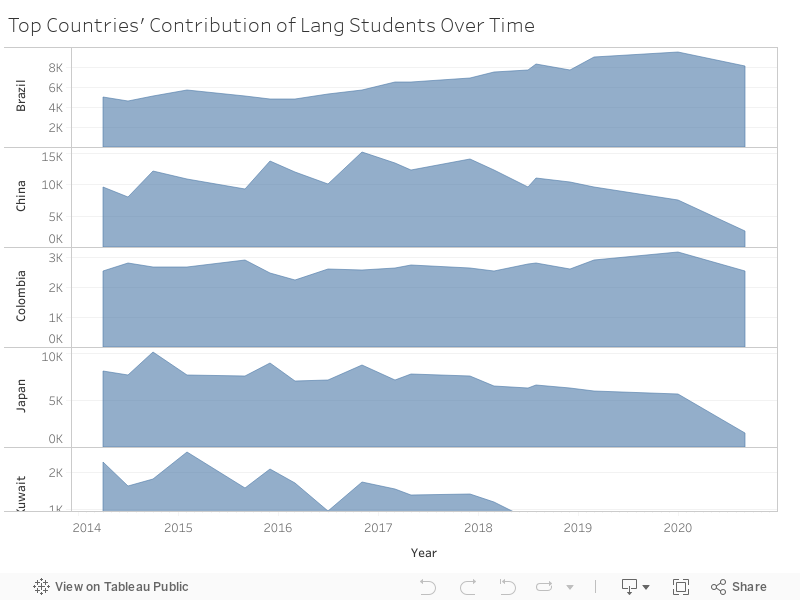

In the last decade, there has been a steady uptick of students from China and surges of government-sponsored scholarship students from Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and Libya. These government initiatives have provided significant but also short-term windfalls to Intensive English Programs.

Most notably, IEPs were the first to be impacted by the curtailment of the King Abdullah Scholarship Program (KASP) and Brazilian Science without Borders (SwB) program, both of which funneled students into degree programs. This early impact earned IEPs the moniker “canaries in the coal mine.”

The Perfect Storm or Climate Change?

The initial effects of oversupply in a maturing market were exacerbated by what was initially perceived as characteristic short-term volatility induced by the end of the KASP and SwB windfalls that began in early 2015.

By 2016, however, it became clear to many that the squall was looking more like a storm, and a perfect one at that. The election of Donald Trump and the ensuing embrace of U.S. nationalism, anti-immigration policies, and uncertainty surrounding the popular OPT program (optional practical training) for STEM graduate students all contributed to the perception that the U.S. was an unwelcoming environment for international students. A booming economy, strong U.S. dollar, and continuing rise in university tuition didn’t help matters. The result was that overall IEP market share quickly shifted to neighboring Canada, which offered students work rights, lower costs, and a perceptibly more welcoming environment.

This is also when we begin to see a divergence and decoupling of the fate of IEPs versus U.S. universities with regard to international student demand, with IEPs’ student numbers declining at an exponentially faster rate. This is true even when considering that SEVP enrollment data for university students includes the “long-tail” of post-degree students enrolled in OPT.

From a long-term perspective, this divergence has more to do with the expansion and maturity of the global English Language Training (ELT) industry than with a decline in the popularity of the U.S. as a destination for university study.

The Effect of the Global ELT Industry on U.S. IEPs

As U.S. universities have begun to see competitive pressure from other countries, they have also seen their share of internationally mobile students decline. In contrast, countries benefiting from a larger share of the international student pie in recent years include Japan, China, Canada, and Australia. This, in turn, has contributed to a decline in the demand for U.S. campus-based IEP programs catering to degree-seeking students.

Independent language schools have also seen downward pressure on revenues as a more competitive and maturing market has resulted in severe price competition and increased commission to agent channel partners. This has put strict constraints on business margins and profitability.

However, the most detrimental, influential, and perhaps invisible force impacting IEPs in the U.S. (and other countries) has been the growth, innovation, and development of the global English Language Training (ELT) industry.

However, the most detrimental, influential, and perhaps invisible force impacting IEPs in the U.S. (and other countries) has been the growth, innovation, and development of the global English Language Training (ELT) industry.

English has become the defacto “lingua franca” of the world, the result of which has been the rise in the importance of English language proficiency for upward mobility, commerce, education, and even GDP growth. It is estimated that there are as many as two billion English language learners across the globe.

The growth of the ELT industry encompasses a variety of different segments, ranging from hundreds of language-learning apps to huge, online education giants like VIPKid and italki, both Chinese unicorns with market caps over $1 billion. Mid-market ELT companies include global transnational online schools catering to the corporate sector, such as Learnship GobalEnglish, Learnlight, and Voxy. The marketplace business model has also been applied to language learning, with online teacher marketplaces such as Preply and Verbling threatening to disintermediate language schools.

In short, English language training is a $50 billion giant that has been systematically chipping away at the market share of IEPs. While it is easy to argue that the concept of an in-country Intensive English Program that provides a cultural, experiential language learning environment is the gold standard, bar none, it is also the costliest solution. Whereas students, particularly wealthy, upwardly mobile students from developing countries, used to include a sojourn at a language school abroad as a rite of passage, this is no longer the case. If and when students do partake in language programs at IEPs, it has increasingly been for shorter stays, at higher levels of language proficiency, and with a dual purpose, such as tourism or other planned activities – “English Plus,” as it has been coined by the language-travel sector.

Student demographics have changed as well. Increasingly wealthy, upper-class, internationally mobile university degree-seeking students don’t require studies at an IEP before matriculating. Today, university IEPs cater to the “last mile” in English proficiency, a costly pit stop for those that need to top off their English before pursuing a degree program at a university.

The future growth opportunity now rests with a developing country market made up of the middle-income class, who may not have attended bilingual schools or had years of language study in their own country, pursuing study at IEPs globally. They seek work and immigration opportunities available to them as students – to learn the language, earn a degree, get work experience, and get a shot at immigration. The ability to work legally while studying, or even post-study, subsidizes the cost of tuition, and this drives enrollment at IEPs in countries such as Australia, Canada, Ireland, and the UK. By contrast, in the U.S., employment is largely restricted to STEM degree students via the OPT program. Will a pro-immigration Biden administration level the playing field, permitting U.S. IEPs the opportunity to tap into this market?

Today, university IEPs cater to the “last mile” in English proficiency, a costly pit stop for those that need to top off their English before pursuing a degree program at a university.

In this context, where a maturing and competitive global ELT industry is successfully making English the world’s lingua franca, that some IEPs might entertain the thought of transitioning recent COVID-19 induced stop-gap measures to deliver instruction online into a permanent or long-term strategy shows a lack of understanding of the fundamentals of the ELT sector. It’s an insular perspective from a segment that is behind the global ELT curve, but whose strength and niche is purposely designed to teach English in the classroom, in the country where it is spoken.

Student Enrollments at IEPs Decline Faster Than Enrollments in University Degree Programs

DATA ANALYSIS

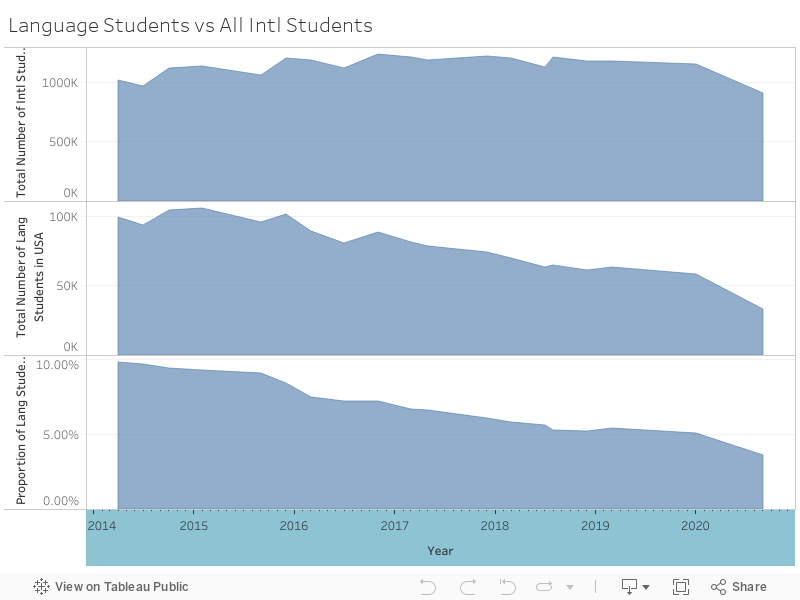

[SEVP DATA SHOWS A 45% PRE-COVID DECLINE OVER 5 YEARS]

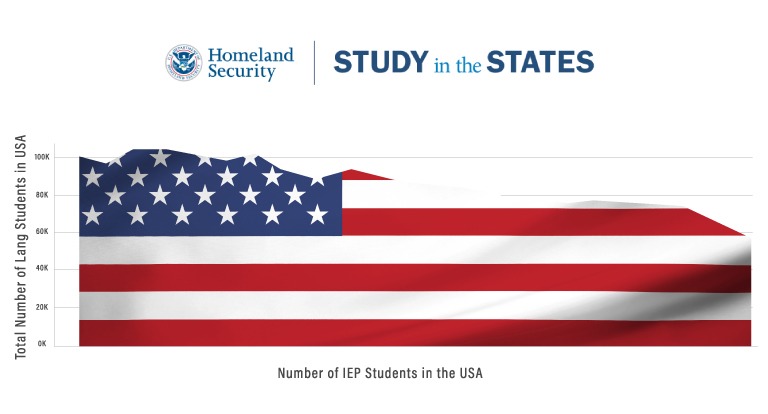

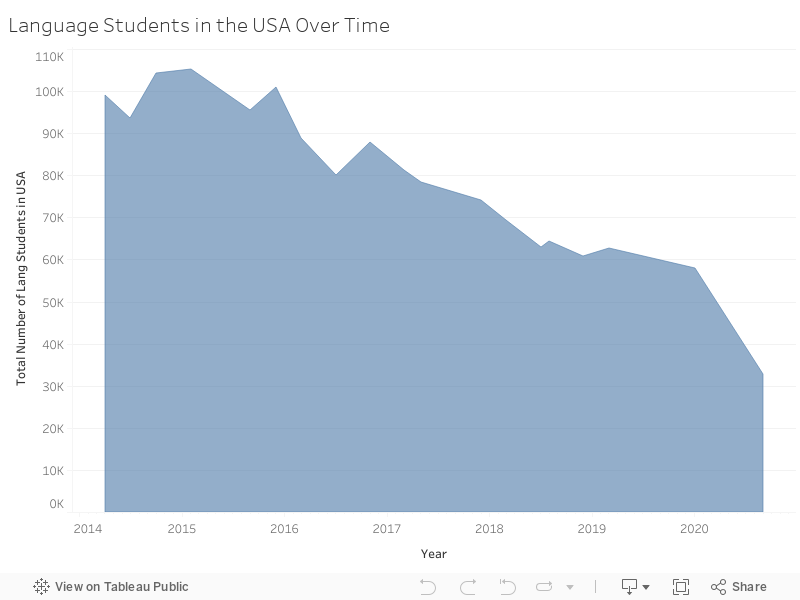

Collecting accurate data on student enrollments at IEPs is a challenge; however, the hard data provided by the Department of Homeland Security, “SEVIS by the Numbers,” provides the most timely and comprehensive data on ESL students enrolled in full-time programs of 18+ hours, requiring an F1 student visa. Although somewhat irregular in its reporting schedule, SEVIS by the Numbers has, nonetheless, provided us with enrollment data as of April 2014.

We should note that the F1 student visa data set doesn’t tabulate as many as 30% of the English language students studying at private sector centers, who often study in short-term, less-intensive programs of fewer than 18 hours per week, which in turn allows them to enter the U.S. and study on tourist visas. Nevertheless, the data set serves as an accurate barometer of the sector’s health, a snapshot of student numbers on a given month and year. It should be noted that students on F1 visas are enrolled in intensive programs for longer stays and represent the higher economic value of students in these types of programs. In the case of IEPs offering Academic English and catering primarily to degree-seeking students at U.S. universities, students on F1 visas can represent 90% or more of their student body.

This SEVP data above shows a long-term, steady decline as opposed to the historic short-term volatility of years past. In fact, the data shows that we’re now in the fifth consecutive year of steady decline in enrollments, a pre-pandemic decline of as much as 45%, from 105,211 students in February of 2015 to 57,923 in January of 2020. This is a percentage drop that would be considered catastrophic in most industries. It is perhaps the historic volatility of the sector that has made it somewhat less alarming, with many long-standing industry players quick to characterize the drop as yet another “temporary downturn.”

This most recent decline begins in 2015, precipitated in large part by the abrupt end of two bonanza programs. Among these was the swift suspension of the Brazilian Science Without Borders (SwB) program, which, in many cases, included funding for three to six months of English study for participants. Initiated in 2011 and expanded in 2014, the SwB funded as many as 100,000 scholarships abroad. Most significant, however, was the drastic curtailment of the King Abdullah Scholarship Program (KASP). Initiated in 2005, KASP was a boon to both private sector and university-run IEPs. The program funded as many as 18 months of intensive English study to Saudi students intent on eventually matriculating at U.S. universities. In addition to funding cuts, changes to the program included initiatives designed to encourage Saudi students to improve their English proficiency prior to obtaining scholarships for study abroad.

The curtailment of these two programs also affected U.S. university enrollments as students’ study at IEPs was a precursor to full-time, full-tuition enrollment.

While the reduction in enrollments from KASP and SwB may have precipitated the overall decline in IEP enrollment, more concerning is a softening in the market fundamentals that points to a more profound downward trend. Together, these were labeled “the perfect storm.” This perfect storm was comprised of several factors, including a steady rise in the U.S. dollar exchange rate (beginning in March of 2015), the exponential growth in the cost of U.S higher education, and the continuous erosion of market share by the global English language training marketplace. Add to this the most recent trends under the Trump administration toward U.S. nationalism and immigration-unfriendly policies including, most importantly, the threat of a cutback to the OPT program. And all of this was prior to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

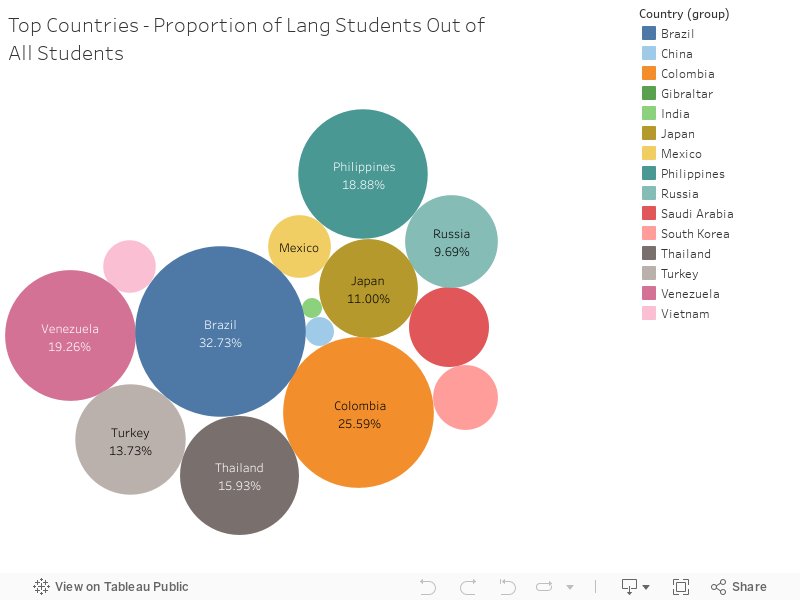

Perhaps more revealing and shocking is the current size of the sector. Students enrolled in language programs comprise only 3% of all international students.

CHART COMPARING SEVP DATA ON STUDENTS ENROLLED IN DEGREE PROGRAMS WITH THOSE ENROLLED IN LANGUAGE PROGRAMS

Excess Supply in a Mature and Shrinking Market

In recent years, beginning even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, an oversupply in student seats has resulted in the financial decline and stagnant growth of IEPs. This decline has, in turn, precipitated shifts in market segmentation as well as the closure and consolidation of schools.

Some of the more high-profile, pre-pandemic closures include the shuttering of ILSC Language Schools U.S. centers in San Francisco and New York City and the sale of Study Group’s Embassy English chain to language teaching chain, EC, both in 2018. These two exits, manifested in one case by a sale of assets and in the other by outright closure, were carried out by private-equity-backed players, indicating, one might easily hypothesize, a lack of overall confidence in the sector’s long-term future.

Shifts in market segmentation, again driven by increased competition, have been manifested in diminished specialization in the types of student personas schools cater to. Traditionally, university programs have focused almost exclusively on Academic English preparation for degree-seeking students; however, most recently, university-run IEPs have begun catering to shorter-term “General English” students and have even expanded offerings to programs such as “English for Au Pairs,” “Executive English” and “English for University Employees,” among others. These English for Specific Purposes programs were, in the past, primarily the domain of private sector IEPs in off-campus settings. Many centers have also supplemented language training tuition revenue with additional service offerings such as IELTS testing and English teacher training programs (TESOL).

Likewise, private sector IEPs have expanded into the turf of university-run IEPs by offering Academic English for degree-seeking students. This shift was driven in part by the surge in demand caused by the KASP, which sought to distribute degree-seeking Saudi students over a wider range of language schools across the U.S. Independent schools were quick to pivot and adapt, making the necessary changes to their curriculum and hiring ESL teachers with the MA TESOL degrees favored by the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission that managed the scholarship program and approved schools.

The expansion of Academic English was also fueled by universities without IEPs on campus as well as by university pathway programs. Both of these, in a bid to increase degree-seeking student enrollment, enlisted the support of independent language schools by offering up follow-through and override commission to originating agents and schools, and TOEFL/IELTS waivers and letters of conditional admission to their Academic English program graduates.

It should be noted that these recruitment partnerships are not so common with university-run IEPs that, in an attempt to mitigate competition by independently-run IEPS, limit the degree path of matriculation to their institution to students exclusively enrolled in their own IEP programs. One might argue, however, that this approach, in turn, reduces the pool of degree-seeking students the university might pull from, particularly in large, urban markets.

The growth of partnerships between the private sector and universities, whereby independent chain schools opened centers on university campuses, further expanded the growth of IEPs and blurred the lines of segmentation. Private sector schools promised to engage in international student recruitment in part because this was a task many universities were not adept at, but also because some universities balked at engaging in success-based commission recruitment models with agents overseas, a practice historically discouraged by the NACAC (National Association for College Admission Counseling).

A second phase of expansion of these private-public partnerships (PPPs), as they are commonly known, came about as university-run IEPs began to face drops in student enrollment and subsequent financial losses. A common solution was to outsource the operation of the IEP to the private sector at a lower operating cost. One rather high-profile case was that of the California State University, Fullerton IEP, which was unprofitable despite enviable student enrollment numbers (from a private sector perspective). It eventually closed its doors without selecting a private sector partner.

The looming shadow of the global ELT industry has also created new customer segments. As students increasingly learn English in their own countries, they enroll at IEPs with ever-higher levels of proficiency, for shorter stays, and in less intensive programs, many times as tourists. As a result, some independent IEPs have slowly begun to look more like travel companies, with their most popular programs being teen summer groups offering English study in the morning and excursions to amusement parks and shopping malls in the afternoons.

DATA ANALYSIS

SEVP Data Exposes an Immigrant-Driven, Private Sector Niche, the “Evening IEP”

Independently owned language schools’ bread and butter has historically been the short-term language student, characterized by seasonality and stays as short as four weeks, seeking highly popular metropolitan cities with tourism cachet. However, there are some new, less traditional, and perhaps lower-profile student segments emerging, which manifest themselves in SEVIS data but also via Google searches such as “English school F1 visa.” This new student segment pursues long-term stays and, perhaps eventually, immigration. Programs titled “F1 Intensive ESL” are offered for as little as $420 a month – one-third the cost of a university IEP. Classes are offered in the evenings from 5:30 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. and even as “two-day compressed weekend IEPs” with classes Saturday and Sunday from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., under which students may meet their visa requirements of 18 hours of study per week. These schedules also leave students with ample time to pursue other activities during the day or workweek.

One such chain, UCEDA, has 11 centers across the states of New Jersey and Connecticut in immigrant-dense, working-class neighborhoods and cities. Similarly, Harvest English Institute, with centers in Orlando, Los Angeles, and other locations, offers a “Premium Intensive English – F1 Visa” program in the evenings, with tuition advertised as 52 weeks for $7,228 USD.

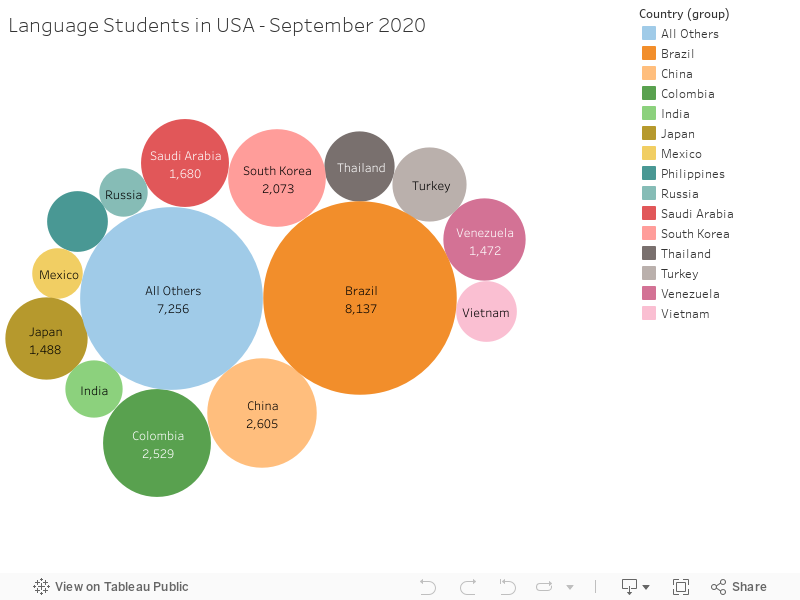

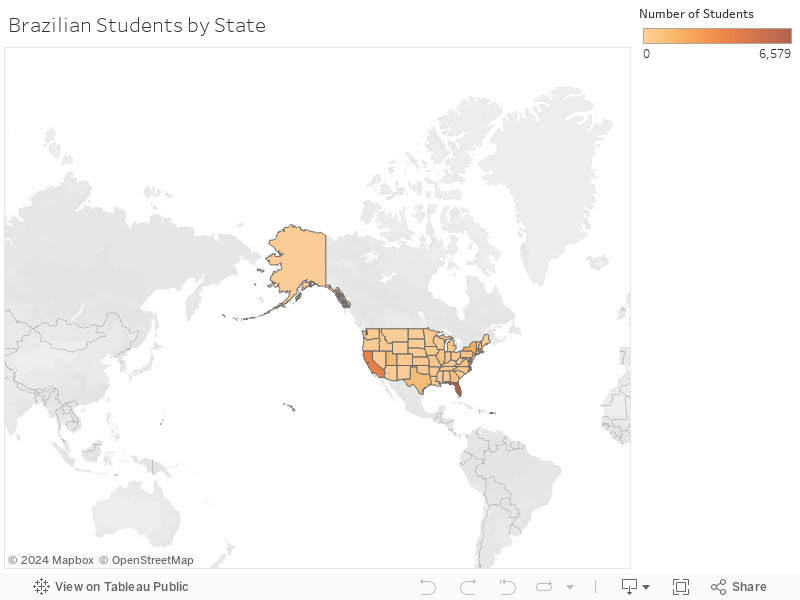

These immigrant-focused programs, in their aggregate, cater to relatively large numbers of students on language-study F1 visas and help to explain the large number of Brazilian, Venezuelan, and Thai students enrolled at IEPs, according to SEVIS data. Not coincidentally, these same nationalities are unique in that they have higher proportions of students studying at IEPs than in university degree programs.

It would also appear that this segment’s enrollments coincide geographically with large immigrant communities of the same nationalities.

For instance, a look at Brazilian English language students with F1 visas shows that almost half the students are concentrated in Florida, a state with the highest number of Brazilian immigrants, as well as California and Massachusetts, two other Brazilian immigrant hotspots.

SEVP data on Brazil’s geographic enrollments in the U.S.

COMPARING SEVIS IEP ENROLLMENT DATA WITH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION (IIE) ANNUAL REPORT

|

TOP 10 SENDING COUNTRIES TO INTENSIVE ENGLISH PROGRAMS | ||

| 2019 | ||

| Open Doors IEP Data (University IEPs) | SEVP by the Numbers student visa data (All IEPs including Private sector) | |

| 1. | China | China |

| 2. | Japan | Brazil |

| 3. | Saudi Arabia | Japan |

| 4. | Brazil | Saudi Arabia |

| 5. | South Korea | South Korea |

| 6. | Taiwan | Colombia |

| 7. | Colombia | Thailand |

| 8. | Italy | Venezuela |

| 9. | Mexico | Vietnam |

| 10. | Turkey | Turkey |

This table compares top nationalities enrolled at university IEPs, according to the Institute of International Education (IIE) annual report and data captured from SEVP for 2019. Note that Thailand, Venezuela, and Vietnam don’t make the Open Doors IEP top 10. Brazil also ranks higher overall on the SEVP data set. This divergence highlights the differences between market segments and shines a light on the demographics of the new “Evening IEP” segment.

What Does the Future Hold? Long-Term and Short-Term Perspectives

Long-term perspectives increasingly tied to U.S. immigration policies

In the context of a global ELT industry that continues to offer international students low-cost, accessible, and practical solutions to language acquisition in their home countries, the growth prospects of the in-country Intensive English Program would seem to be permanently threatened. Furthermore, as foreign governments improve English instruction and introduce programs such as CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) in public K-12 schools, this too will affect the long-term demand for private sector delivered English programs, including IEPs.

As IEPs (and pathway programs) increasingly position their programs as a gateway to higher education, their fate is similarly tied to the overall success of U.S. universities in attracting international students.

For both groups, however, the single most important influence on their prospects lies with government immigration policy. Today, students face a policy whereby simply indicating “dual intent” – the notion that the student might not only like to study in the U.S. but also eventually immigrate – is grounds for rejecting a student visa application.

However, current initiatives, led in part by the American Council on Education, highlight that the U.S. is in need of a proactive national strategy to attract international students, one that recognizes the value they can deliver to the country’s intellectual and economic growth. Such a policy, which actively and openly encourages study in the U.S. as a path to immigration, while also permitting students to help fund their studies with work permits, would give the U.S. the competitive advantages enjoyed by the sector in Canada, Australia, and other countries.

Such policies could be a game-changer for IEPs as they attract the upwardly mobile, middle-class students from developing countries who may not have the English proficiency of the global elite (that attend international bilingual schools) the U.S. currently attracts to its campuses. These students would benefit from the cultural immersion and English language training that IEPs can provide and at costs subsidized by the ability to work and study in the U.S.

The pandemic: Short-term prospects and The Stockdale Paradox

2020 delivered a blow to the IEP sector already battered by a steady five-year decline in enrollments. As we begin 2021, it should be clear that the sector is still not out of the woods, with even the most optimistic forecasts suggesting coronavirus vaccines will still not have been delivered to the populace at large before July of 2021.

If anything, the COVID-19 pandemic will have the definitive effect of downsizing the IEP marketplace and eliminating the oversupply that has plagued the growth and prospects of the industry for so many years.

Those currently in the sector should now be thinking about how to prevail in times of crisis, and in that context, we might do well to understand the “The Stockdale Paradox,” which was coined by Jim Collins in his timeless business read, “Good to Great.” Collins relates the story of Admiral James Stockdale who, as a POW during the Vietnam War, noted, “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end — which you can never afford to lose — with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

As it relates to his experience as a POW, the question to Stockdale was “Who didn’t make it out?” to which he responded, “The optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart…”

You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end — which you can never afford to lose — with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.

-Admiral James Stockdale

The IEP sector has always been a collegial and close-knit community, even on a global scale. The point is that this crisis will require more than moral support and wishful thinking for a brighter future. It will require a level-headed assessment of the challenging realities the marketplace is throwing its way.

Additional SEVP Data