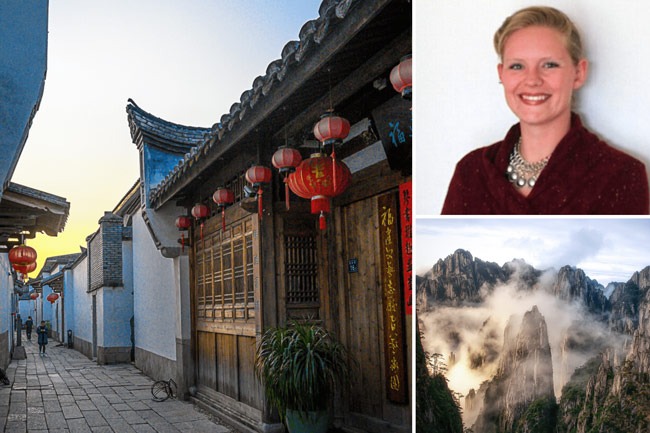

This article was written by Coleen Monroe-Knight, a Bridge grad who has been teaching English abroad for over 10 years. She currently lives in Fuzhou, China, where she was teaching English when the coronavirus pandemic first hit. Like many teachers worldwide, Coleen’s classes suddenly moved online, as the center where she taught temporarily shut down. Recently, however, it has reopened and Coleen and her students have returned to the classroom. We asked her to describe her experience in China during coronavirus– from lockdown to cautious reopening.

13 January 2020 marked eleven years of living abroad for me, nine of those spent teaching English as a foreign language in Vietnam, China, Chile, and South Korea. 23 January 2020 marked the beginning of the lockdown in Wuhan, China and the beginning of the new normal. This year has been a strange one for many people, but for those of us who happened to be living and working in China, it has been a big ride. I’m Coleen Monroe-Knight, and I’ve been living in Fuzhou, China for more than a year and a half. I work for a medium-sized English teaching company and teach children/teens.

Onset of the COVID-19 lockdown in China

The first email that I got from the US State Department (always sign up for STEP notifications, kids!) about what would come to be called the coronavirus, or COVID-19, came through on 31 December 2019. People were on edge as we prepared to go on the Chinese New Year break. Masks were beginning to sell out in the supermarket downstairs, and it was getting harder to find soap and hand gel. Our last day of teaching in person was 22 January. We said goodbye to our office mates and said, “See you next week!”

We didn’t know that it would be 168 days before returning to the classroom in China during the coronavirus crisis.

I was traveling to Beijing for the Chinese New Year celebrations on a high-speed train when the notifications that Wuhan was quarantined came through. My husband and I fretted for several days in the capital about whether it would even be possible to get back to Fuzhou, as more and more ominous warnings piled into our email inboxes and the situation became much more serious.

On 29 January we took the almost totally empty train back to Fuzhou and went into confinement in our apartment. Lockdown was never as hardcore as it appeared on the news in our area; it was possible to go outside at all times, there weren’t any food shortages, and toilet paper was always available. We began our emergency remote teaching two weeks after Wuhan was quarantined, returning remotely to the classroom in China during coronavirus crisis after the extended holiday.

How schools in China adapted to online learning

In terms of teaching, we were somewhat hampered at first by the sheer emergency nature of being remote during a wholly-unexpected lockdown. Some teachers didn’t have a laptop or a computer that they could use, and no one was allowed to meet in person to swap ideas or get books that we needed from the office. We set up with an online education app and began to plan our lessons with our Chinese colleagues via WeChat, starting with a couple of weeks of free review lessons and moving into teaching actual content in late February.

Our curriculum was halved to make it less pressure for everyone’s brains. We taught half of a lesson each meeting. Some classes were cancelled outright because parents refused to allow their students to learn remotely. There was even a little pressure from some parents to provide in-person lessons when it was definitely illegal to do so. We didn’t.

Our city moved cautiously when it came to opening back up. By early March it was possible to get take out from almost any restaurant and office workers were mostly back to being in their workplaces. Schools remained closed. We made a lot of adjustments to the curriculum to accommodate the situation including scrapping most tests and asking for more parent involvement in home learning. There were mixed results in terms of whether this worked; a lot of parents simply wouldn’t send their students’ homework or refused to make time for class.

Foreign teachers’ situation during the crisis

As you might imagine, there was a lot of pressure on those of us teaching in China as foreigners to go home or to get out of China in the early days of the pandemic. Governments issued the most severe travel warnings that they can give, and in the case of the UK Foreign Office directly appealed to citizens to return home. Many teachers left or did not return from abroad, where they had been vacationing during Chinese New Year. In early March, the situation began to flip. The outbreaks in Italy, the UK, the US, and elsewhere outside China began to shift the focus off us and toward our other homes.

By late March, our province had no community transmission. But the risk was still considered too high for children to return to their classrooms, due to outbreaks of COVID-19 in the north of the country and an increase in imported cases from abroad. On 28 March, the Chinese government closed the border to all non-citizen international arrivals to slow the imported cases. That meant that anyone who had been working remotely from abroad could not return.

Things ground along for three months with more or less no changes. We mostly stayed indoors and taught remote lessons online, and didn’t see our colleagues except in Zoom meetings once a week. By mid-May, we were asked to take and report our temperature every day to help the schools to reopen with permission from the local government. A slight uptick in anti-foreigner sentiment affected our planned holiday in late May, because hotels were afraid that we had somehow gotten past the border since it had been closed in March. This has since mostly dissipated.

In early June we all had a nucleic acid test. On 11 June, Beijing reported a serious but small outbreak of Covid-19 in the capital due to infections at a major food market. This probably slowed our returning to the classroom because officials around China were watching out to make sure that the spread was limited. It was fine with me, because in many ways I didn’t feel ready to go back to the classroom. It is difficult to watch the news from the rest of the world and remember that things are currently different here in our province. Our families are in hard-hit countries and our media is saturated with the worries of the US/UK for coronavirus, so it’s hard to remember that we are relatively secure here.

Reopening of Chinese schools

In early July we opened the school.

We got a memo from our work about the social distancing measures that needed to be in place, including:

- Masks for all students and teachers during lessons

- Temperature checks on arrival for students and parents

- Frequent hand washing

- Keeping 1 meter apart (the China standard)

- No parent showcase lessons, no parents/guardians allowed on the premises during lessons

Most of the rules are followed at our school, but the procedures are not fully followed. Parents stay inside the school after classes begin, sometimes without masks. This makes me uncomfortable but my concerns have been dismissed by our managers because of the lack of any contagion in our area for several months. I take full precautions and insist on social distancing in my classes because I fall into a high-risk category. I don’t want to be caught flat-footed. It’s not like people in Beijing knew they would be going back into lockdown last month, so it could jump up and surprise us here, too.

Other than the niggling worries, the return to the classroom has been a good one. It’s so different to be able to share the space with the students. I felt hugely energized and happy last week, even with all the necessary changes to class and curriculum. There are many reasons why I’ve been teaching abroad as long as I have, and it was great to be reminded of them!

Making headway as classes resume

Since we’ve returned, some classes have been cancelled for low attendance. We teach the same number of lessons every week as ever, but we only see the groups of students once a week instead of twice. This is to help the schools to cover all the lessons with the staff available, since too many teachers left China at the beginning. It’s been an adjustment, but overall it’s good. Our school has also sold off part of the school to other businesses so that we don’t keep space we don’t need. Given that our foreign teaching staff and sales staff have been reduced by more than 50%, we clearly don’t need the full complement of classrooms we once did.

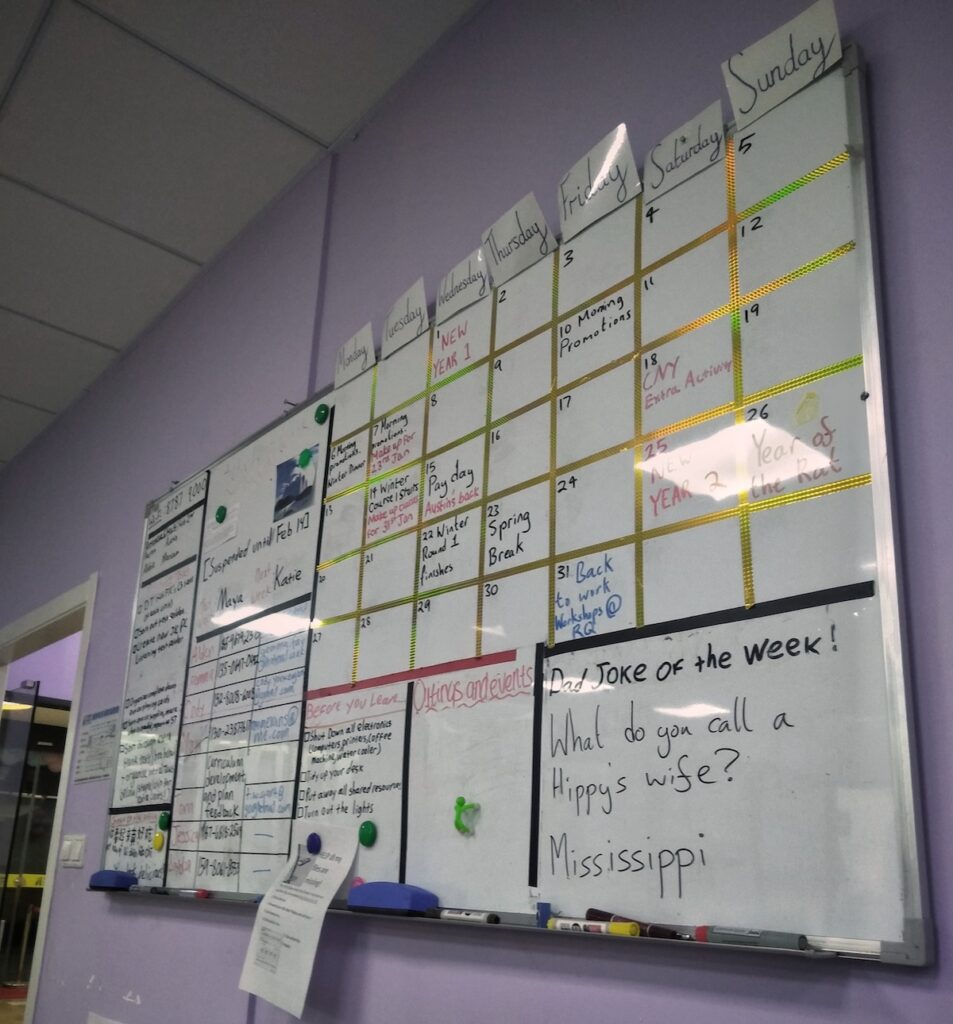

My husband said last week, “There are too many ghosts in here.” He’s right. The school feels very quiet most of the time, and it was strange to come back to the office that still had everything set up as if our colleagues would be returning. Everyone’s desks still had our unused calendars for the week after Chinese New Year, tests piled high in stacks, and boxes of teaching materials. As if we’d all be here on 2 February as planned. There are even Christmas sweaters on the chairs. Slowly, I’m cleaning the office in planning hours and removing the calendars that still say January. It’s better to imagine that we came to a completely new school and not think about how much things have changed and who is missing.

We plan to stay in China and continue teaching English. Our decision to stay when our governments told us to leave paradoxically led us to find a safe place to be in this remarkable year, and I feel secure knowing that if cases began to spread in our area we’d react quickly and be able to stop the spread. This will be the first year since 2009 that I won’t spend time on more than one continent, and the ability to travel that drew us to this lifestyle in the first place is significantly curtailed. But we have jobs. We’re safe. We can teach. It’s a pretty good year, by 2020 standards.

(If you’re reading this and have questions about teaching in China at this time, I’d be happy to help answer them! Feel free to contact me via my Gravatar profile.)