At the start of the pandemic, the world came to a halt. Formerly bustling cities were suddenly marked by empty streets, closed businesses, shut down schools and at-capacity hospitals. The “new normal” of life during COVID-19 became not only a learning process, but a creative one as well. For more than 168 million children worldwide, schools closed for almost an entire year, according to a UNICEF analysis. One in seven children missed more than three-quarters of their in-person education.

English as a second language (ESL) learners and teachers confronted even greater challenges, with estimates that English learners (ELs) fell 14 months behind in instruction, according to Migration Policy Institute (MPI), a think tank on information and analyses of international migration and refugee trends.

Dr. Cynthia Kilpatrick, a teacher of Spanish and English as a second language has been on the faculty of the Department of Linguistics and TESOL at the University of Texas at Arlington since 2009 and joined UTA’s English Language Institute (ELI) as the interim director in 2016. Kilpatrick said the pandemic has resulted in a variety of challenges at the institute.

Dr. Cynthia Kilpatrick, director of the University of Texas at Arlington English Language Institute

“First, our student numbers have decreased drastically because it has been so difficult for students to get visas and come to the U.S.,” Kilpatrick says. “This means that we have also had to reduce our teaching staff.” She says moving online was a difficult adjustment for teachers and students, but they found ways to make it work. “We have had to combine multiple levels into a single classroom, so students and teachers have had to adapt to having a wide variety of proficiency levels in each classroom,” she says.

“One thing that I have really learned is that we can teach English effectively online! For many years we, the field of ESL teaching, have resisted moving online, thinking that an online modality was not going to be effective. But when we were forced to try it, we found that it worked. I think that this discovery has the potential to change the world of ESL teaching if we allow it to, and I look forward to seeing how the field grows and changes over the next few years.”

According to the World Bank, the worldwide school closures resulted in a $10 trillion loss of lifetime earnings for the young generation of students globally. And that young generation, according to UNICEF, included 1.6 billion learners, equaling approximately 91% of the world’s enrolled students. English learners were hardest hit by the disruptions of COVID-19. “In many cases, virtual learning effectively foreclosed opportunities for English learners to engage in English-language conversation with adults and with peers, receive intensive language instruction at frequent intervals, and encounter conversational and formal language in a range of social and academic contexts,” according to a report published by the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.

The loss of human interaction because of the pandemic created a need for education to assimilate quickly or stagnate. Kilpatrick says at UTA teachers were immediately offered professional development. “UTA offered a wealth of trainings, support and help, and I have encouraged our teachers to attend and watch these. I also made a few screencasts early on to help teachers who were not familiar with Zoom,” she says. “The ELI teachers have always provided excellent instruction for ELI students. I have been impressed with how they were able to pivot online in March 2020 and really create an excellent learning experience for our students, even those who had gone home and were in vastly different time zones. Through much of the pandemic, we taught most of our classes online, and we felt that this was very successful.”

Kilpatrick says, “One thing that I have really learned is that we can teach English effectively online! For many years we, the field of ESL teaching, have resisted moving online, thinking that an online modality was not going to be effective. But when we were forced to try it, we found that it worked. I think that this discovery has the potential to change the world of ESL teaching if we allow it to, and I look forward to seeing how the field grows and changes over the next few years.”

Audrey Mislan, has taught K-12 and higher education for 26 years. She has incorporated ESL strategies into her classroom in Florida. She says teaching online is a transition that found students having a difficult time focusing and teachers adjusting to a new teaching method.

“Public education at K-12 level had the hardest time adjusting because teachers weren’t used to using software such as Zoom to conduct lectures,” she says. “The structure many schools used often forced teachers to sit for long hours in front of the screen, which had a negative impact on the teachers and their morale. Many schools also mandated extra teacher accountability measures and student tracking, which meant more work for the teachers.”

Teachers were provided with “best practice” professional development to help with the transition. However, she says she still struggled with feeling confident on using the software to deliver engaging lectures. “As an instructor, I think online, virtual learning works well for students who are self-motivated. This typically develops in younger students through in-person classroom experiences,” she says. “As students get older and develop a love of learning it becomes easier to get students to want to do assignments.”

Remote learning options became the only possibility for sustaining education. Three-fourths of teachers were required to teach during school closures, according to a study by UNESCO, UNICEF and the World Bank, which surveyed 149 ministries of education on their responses to COVID-19. Nearly every country in the survey reported using online platforms, TV/radio programs that aired educational programs and/or take-home packages, which were distributed to students to help them continue learning.

A Shift to Online Learning

According to UNICEF, globally 2.2 billion young people 25 years old or younger, or two-thirds of the individuals in this age group, do not have an internet connection at home. More than two-thirds of school-age children between the ages of 3 and 17, and 63% of those aged 15-24, lack internet access at home.

Organizations like the National Association of English Learner Program Administrators (NAELPA) supply resources to educators working with ELs. NAELPA created a dedicated website for teachers and administrators to help bridge the gap by providing resources and information on teaching English online during the pandemic. Organizations like Migration Policy Institute offered insights for educating English learners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, online resources appeared to take hold of English language learning. In Nepal for example, the Curriculum Development Centre provided teachers with curricula, textbooks and guides to assist with virtual English language teaching. With the immediate need for professional development, teachers turned to online resources like the British Council’s website and the U.S. Department of State’s American English website.

Today, mobile phones, laptops and tablets create a modern-day classroom environment through Zoom, Google Classroom, Microsoft Teams, Canvas, WhatsApp, Telegram, Edmondo and a variety of apps and ed tech blends that all require one key ingredient: electronic connectivity. However, MPI estimated that more than half of ELs had difficulties with digital technology and remote learning resources, while teachers simply lacked the opportunities for training. A study of English language professional development of teachers in Nepal during COVID-19, conducted by Ganga Ram Gautam, found that teachers sought out development on their own. “There was an unsurmountable pressure on teachers to make a shift to the alternative mode of teaching as quickly as possible, but there was no organized support system in place for teachers to learn the new ways of doing. The situation brought confusion among teachers, putting them in a very stressful situation,” according to the study.

A lack of resources and electronic connectivity was problematic for much of the world.

UNESCO and the International Telecommunication Union estimated that 43%of students whose schools were closed as of May 2020 did not have access to the internet. While the main approach to ensure the continuation of education was the use of online platforms, in 95%of the countries, many low-income countries were forced to use broadcast media — 93% used radio and 92% television for education purposes. According to UNICEF, globally 2.2 billion young people 25 years old or younger, or two-thirds of the individuals in this age group, do not have an internet connection at home. More than two-thirds of school-age children between the ages of 3 and 17, and 63% of those aged 15-24, lack internet access at home.

Socioeconomic factors explain this picture further. Only 5% of young people under the age of 25 in West and Central Africa and 13% in South Asia and Eastern and Southern Africa have internet access, while in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 59% have access. In short, the richest households had universal access at 97%, while 74% of the poorest households had access.

Global Community Responds to Online Learning

The pandemic brought social interaction to a halt, a tremor felt deeply by language learners who often require social and academic interaction to become proficient. Various studies found a discord of opinions about virtual learning of English as a foreign language (EFL).

- Mohammed Mahib UR Rahman found that teachers in Saudi Arabia enjoyed the fact that online classes saved time and could be conducted anywhere. However, 56%t of the respondents liked face-to-face classes better, and 68% believed students were less motivated during online classes. Eighty-six percent of the teachers found maintaining discipline in large classrooms challenging , and 78% of the teachers had difficulties teaching specific skills like writing.

- In Germany, Holger Hopp and Dieter Thoma found the school closures during the pandemic did not appear to have harmful effects on overall foreign language learning among young students.

- In another study on EFL in Saudi Arabia, Mohammad Mahyoob found that during the pandemic, technical, academic and communication challenges resulted in English language learners’ dissatisfaction at not being able to meet expected progress in language learning proficiency.

- Brenda Anak Lukas and Melor Md Yunus discovered that in Malaysia students felt unfamiliar with online learning and struggled with poor or no internet connection, while teachers’ technology readiness and competence was one of the main challenges. Students of EFL appeared to have had difficulty learning writing during the pandemic. Speaking in a virtual class environment made students uncomfortable, while peer interaction was difficult.

Kilpatrick says students have been successful overall in the new online format. “I think that both teachers and students miss the social side of being in the same room with their students, but the English language learning side is working well virtually,” she says. Adopting a synchronous classroom model, where students are required to attend scheduled lectures and meetings, she says, helped the English Language Institute move forward. Students were not left to an asynchronous model, where students practice materials and learn skills on their own time. “It’s crucial for language learners to get extensive exposure to the target language, and a synchronous model continues to provide students with 20 hours a week of English language exposure,” she says. “An asynchronous model would not effectively provide this exposure to oral English that our students need, nor would it allow them to practice their English in a safe classroom environment.”

Kilpatrick adds that adopting a synchronous model allowed students and teachers alike to adjust well to the new virtual environment. “As we move forward, I think it’s going to be difficult for students to adjust back to a full, face-to-face model, but of course we will do whatever is required by USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) for international students,” she says. “I think a bigger concern is the continuing pandemic, especially as new variants develop and numbers start to rise.”

While Kilpatrick says she was impressed with how successful some students and teachers were in pivoting to an online environment, other teachers of EFL reported struggling in the wake of the pandemic’s influence. Retired teacher and current private tutor, Nataša Šegvić, from Croatia, has taught Italian and English as a second language for the last 55 years. At 80 years of age and equipped with 35 years as a language teacher in high school, she has seen many changes over the decades. “In Croatia, the students accepted it well. But I believe this generation will have a hole in their knowledge. Learning online is not the same as face-to-face,” she says. “There is a big difference and face-to-face contact is important.”

Šegvić says she witnessed this with students she knew to be excellent, who seemed to lose understanding during the pandemic and continue to make the same mistakes. “If something is not communicated, you can’t expect them to learn it. Learning online, they simply could not comprehend some of the material they were taught,” she says. “It was worse in rural areas where internet connections were difficult, and the economically challenged families didn’t have an internet signal or even a computer or tablet on which to learn.”

While she says she is nostalgic for the past, she also welcomes forward thinking. “Even though I am from an older generation, I believe modern technology is wonderful and necessary in the future when these students grow up and work,” Šegvić says. “However, technology must be given to kids in doses.”

Language learning, she says, needs human, face-to-face interaction. “Students are individuals, and they need individualized lectures when learning languages. We can’t discriminate against those who struggle; we need to help them do their best. Teachers, professors and students need to work a lot on themselves to complete and inform themselves.”

There is room for technology, but when learning a second language, technology has distanced and handicapped language learning, she says. “The communicating being done through texting is creating a strange, informal and deformed language and is creating a world where we do not talk in complete thoughts. It is alienating.”

“Learning loss,” defined as a specific or general loss of skills or even a reversal of academic knowledge, was an issue for almost all students, with the suspension of in-person classes affecting 95% of the world’s population. Language learners had the extra hurdle of attempting to learn a foreign language through a screen. It took a village. Governments scrambled to help schools, students, teachers and parents. The U.S. Department of Education published a fact sheet on May 18, 2020, in regard to services to English learners during the COVID-19 outbreak, which indicated testing for English language proficiency would be waived due to the national emergency. The Department encouraged collaborative creativity between parents, educators and administrators, stating that the Department “recommends continuity in providing language services to ELs to the greatest extent possible under the current circumstances.”

The Office of English Language Acquisition provided a webinar for teachers to assist with training. State governments and private organizations attempted to do the same. For instance, the Department of Education in Louisiana created a document specific to EL education during the pandemic, offering resources for teachers and families. The Texas Education Agency provided detailed guidance for implementing EL summer schools. Organizations like Colorín Colorado, a national organization providing free, research-based information for ELL and educators, created resources specific to the learning environment during the pandemic. Teachers turned to personal professional development by accessing online resources like the English Listening Library Online (ELLO), Voices of America’s Learning English, American English and National Geographic Learning. Interactive websites such as BusyTeacher, ESL Video, Starfall and English Media Lab provided teachers with ideas, exercises, quizzes and materials to keep EL students learning in an engaging and fun environment. Ed-tech companies offered their services for free, in order to mitigate the halt in face-to-face learning. Schools found ways to take teaching into the homes of their students, and teachers found ways to reinvent themselves.

Teachers Collaborate and Create New, Successful Learning Environments

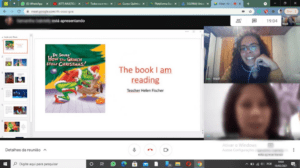

Helen Fischer has been a teacher for four years, two of which have been during the COVID-19 pandemic. Two years ago she received her degree and finished her certification as an ESL teacher through Bridge’s Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) course. She has spent her time teaching both online and in-person for language schools in Brazil and as a private teacher.

Helen Fischer, only two years into teaching, went from working with in-person to virtual students.

“There have been some good changes,” Fischer says. One of those was a shift in students’ mindsets and their opening to the possibilities of online learning. “Before, most of the students thought it wasn’t possible to learn anything on the internet.”

Being forced into an online classroom created a new realization: Learning languages online was possible, and exciting tools existed for students and teachers alike. “They had to get their first taste, and then they were more open to the idea,” she says.

However, Fischer says it was difficult dealing with various platforms, internet connection problems and students and teachers not being technologically prepared for online learning. “Some of my students, my older students, wanted me to call them on the cell phone because they couldn’t deal with the internet, so it was kind of difficult at the beginning,” she says.

For Fischer, most students she has taught still prefer in-person learning, but she sees a future in online education for language learners. She says it allows students the opportunity to use free time between meetings and school to study at their own pace and place.

“The good thing is that nowadays they have a lot of apps and platforms,” she says. “But for me, as a private teacher, I can’t pay for all of the platforms that I would like to acquire because it is too expensive. So, we have to choose platforms that are not so pricy and juggle between what would be best for our students.”

Fischer says a blended approach of part online and part in-person learning would be most helpful, but what she has seen called “blended learning” at this time boils down to one class with some students in school and others watching from home. She says it is with innovation and creativity that she has managed to get through the pandemic. She and fellow teachers started a conversation group where the students in various countries like Brazil, Kenya and Russia would meet and talk while practicing their English skills.

“It’s amazing possibilities that have opened up for us,” she adds. “I’ve seen amazing teachers and ideas that helped me improve, and I would just like to say I love all of the teachers. All of us are struggling, but it’s been good so far. Teachers are very resilient.”

As the coronavirus modified the world and safety protocols put a “do not disturb” sign on our doors, teachers like Fischer and Mislan found ways to innovate and keep students learning. A Globe and Mail article published on February 9, 2021, argued that foreign language teachers modified learning tasks, accommodated students with appropriate assignments based on their level, shortened complex tasks and used Google Translate to provide dual language instruction in order to clarify assignments. Teachers also found it was necessary to focus on social well-being and provided students with ways to express their feelings about the pandemic, missing school, technology issues, while incorporating their own home lives and storytelling sessions to engage students.

Concurrently, they became IT support for students by sharing strategies on using technology and worked alongside the students, introduced them to breakout rooms, reading buddies and games like Kahoot. Addressing the awkward social aspects of speaking on camera and socializing through a computer was an additional hurdle, especially when it was done in a foreign language. Mislan says, “Sometimes students didn’t know what questions to ask because they felt uncomfortable on camera. Students may not have completed prior assignments, creating a cascade effect where it is difficult to catch up on missed work.”

A common component among teachers was the silent, avatar photo student they had to find, manage and engage.

Justin Walker served his country with the U.S. Army for six years, fought in a war and is now dedicating his life to teaching English abroad. For the last 13 years, he has taught in countries like China, Japan and Indonesia and has himself learned to communicate in six different languages. His love of his students and teaching lead him to teach in many different schools, but today he works for Wall Street English in Indonesia, a school with a customized curriculum.

Walker says the pandemic created difficulties with ESL education in particular. He saw the same problems many teachers address. Younger students had issues with technology, cameras weren’t on, parents were not around to assist, schools struggled with curriculum and teachers were left to play roles of teacher, IT expert, manager and more in order to keep their students engaged and to meet their needs. While he says he easily adapted to teaching online, he can’t wait to go back to the classroom.

“I miss my students,” he says. “I used to do spelling bees and drama classes. I can’t wait until that comes back. It’s really put a damper on students’ soft skills and being able to focus.”

Justin Walker (right) with Indonesian ESL students during a spelling bee.

Walker says the difficulties that came with teaching online were most felt by the students who had problems with internet connections or engaging with and responding to teachers. Teachers, on the other hand, he says, were not provided with appropriate materials and found themselves feeling exhausted.

“COVID-19 really hurt our society and students are missing out on a lot,” he says. “It’s horrible.”

Walker says he found a way to continue teaching by creating interactive games for the students and giving his personal material to the students at no cost. “Things have adapted for the better part in teaching English. But students were thrown into things, especially for the first year. It was horrible for some students. And some teachers had never taught online,” he says.

In Walker’s opinion, online learning did bring some interesting interactivity for the students, but like Šegvić, he says too much was lost with regard to interpersonal communication and connection. “It is not sufficient for students to learn online. Especially for the younger kids,” he says. “They are missing a lot of soft skills. Hand-eye coordination, cue cards, things like person-to-person interaction. They are missing a lot.”

Walker says Indonesia is on lockdown again and he fears that the education sector is in dire need of transition and assistance. He says the ESL students have suffered a great deal by being forced to stop learning in a classroom. “You’re losing humanity. That’s why I wanted to be a teacher. To be able to learn from others,” Walker says. “With teaching, I learn from you, you learn from me. That’s why I love teaching. Interpersonal lessons really do help. Having lessons online helps, but not a great deal and if we continue on this path, it’s not going to get better. It’s going to get worse. There will be a great gap in learning ability. You will see some achievement but you won’t see as much achievement as you would in the classroom.”

The Council of the Great City Schools, an organization representing needs of urban public schools, states that English language learners experienced “disproportionate distress” with the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. The U.S. Department of Education confirmed this finding with a December 2019 report that stated teachers of English language learners reported fewer hours of professional development with digital learning resources than other teachers. Even in May 2021, schools in 26 countries were closed country-wide. World Bank estimates the life cycle earnings of students globally will be greatly affected by the shutdown – $16,000 of potential earnings over a student’s work life will be lost. This is not even considering current and future shutdowns. World Bank states, “Before the COVID-19 outbreak, the world was already tackling a learning crisis, with 53% of children in low- and middle-income countries living in Learning Poverty—unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10.”

English language learners trailed traditional students even prior to the pandemic. According to federal data, in 2016, 67% of students with limited English skills graduated from high school, whereas the graduation rate for all students was 84%. But according to a report by the Council of the Great City Schools, it was teacher cooperation that came to the forefront through the use of collaborative sessions, webinars and co-teaching protocols and opportunities with videoconferencing. A critical need for professional development in virtual tools found teachers unprepared. “To address these challenges, many districts quickly deployed systemwide professional development to support teachers,” the report states.

As of July 22, 2021, UNESCO’s live global monitoring of school closures shows most countries to be fully or partially open, or on academic break. Only eight countries are under country-wide school closures due to COVID-19. Universities appear to be heading in the direction of reopening. The Institute of International Education findings in their COVID-19 Snapshot Survey Series indicating that “New survey data finds that U.S. institutions are focusing on bringing students back to campus, with 86% planning some type of in-person study in fall 2021.” For grades K-12, uncertainty is still present and states are faced to make the decisions on whether to open classroom doors.

As the students, teachers and parents cautiously ease back into education, a sense of quiet optimism resounds. With the baptism by fire period completed, students and teachers appear to be prepared to move on.