Education systems in Latin America are prioritizing English language proficiency as a necessary skill for graduates to be equipped for success in an increasingly globalized world, according to a report from the Inter-American Dialogue think-tank, which covers several policy areas in every geographical region from Canada to the southern tip of Chile.

In the last ten years, “more than half a dozen” countries in Latin America have set up national English Language Learning programs in public schools, and several others also offer English language classes in schools, despite having no centrally coordinated program, as cited by the report, Work in Progress: English Teaching and Teachers in Latin America.

Given the huge geographical size and the cultural and economic diversity of the region, what this push to increase English language skills among public students looks like varies depending on each country’s education system, financial resources, and established priorities. However, in countries that have measured the results of investments made in these English as a Second Language (ESL) programs, one main challenge has emerged: recruiting and training highly qualified teachers in public schools.

Bridge Education Group was recently involved in two government-backed initiatives in Mexico and another in Nicaragua to provide continuing professional development in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL). The programs were aimed at equipping teachers in these public-school systems, who are most often lower-level, non-native English-speaking teachers (NNESTs), to improve their English language teaching skills through online, accredited TEFL/TESOL certification.

BridgeUniverse spoke to the institutions responsible for these government initiatives as well as to experts on English language teaching policy in Latin America to learn more about the challenges and benefits of TEFL/TESOL training programs in the region as a whole and in Mexico and Nicaragua in particular.

As demand for teachers rises, the need for ongoing training increases

While it is good news that English programs are expanding across the continent, increased demand for teachers to fill positions in public schools, according to a 2017 report covering 10 Latin American countries, was found to have led to overall reduced English proficiency and teaching skills among public school EFL teachers. Education systems have had to achieve a balance between maintaining high entry standards for the profession and the ability to fill open positions and provide classes to students throughout each of their countries. The need is often met by employing less proficient teachers who will need further professional training to meet these standards.

Most countries in Latin America have language requirements for the recruitment of EFL teachers, but, according to the 2019 Inter-American Dialogue report, systems can be lacking when it comes to enforcing and assessing the required standards. As a result, “many, if not most, English teachers in Latin America lack either the necessary English skills, the necessary pedagogical skills, or both, to be effective educators in the classroom,” according to the report’s key messages.

The need for teacher training to both increase English language proficiency and boost the skills to effectively teach ESL students in the classroom, has therefore increased. Each country in the region approaches this professional training in a unique way and, typically, uses a variety of providers for teacher training. This brings the additional challenges of keeping track of progress and results and measuring whether the investment made, within systems often strapped for resources, has been worthwhile.

“The state or the government is one provider through the Ministry of Education, but also private foundations, universities, and NGOs. So, there is a really wide set of providers, and unfortunately, very little information on what the quality of that training or its impact has been,” Sarah Stanton, Senior Associate, Education at the Inter-American Dialogue policy center, told BridgeUniverse in an interview.

Government teacher training programs align with Bridge’s mission to empower global EFL teachers

Bridge has recently partnered with three different ELT training initiatives in Latin America, all of them under government and regional programs for training English language teachers within these public-school systems. “Working on projects like this very much aligns with Bridge’s values and our mission. We are striving to deliver affordable and accessible training to teachers worldwide, and these programs have been a great opportunity to do just that,” said Andrew Johnson, International Outreach Manager at Bridge, who coordinated the programs with each of the three institutions.

“Many English teachers around the world don’t have access to or knowledge of good professional development opportunities that can not only benefit them in their career but also benefit the end student,” Johnson explains. “We wanted to work closely with these partners to ensure these groups of teachers received top-notch teacher professional development at an affordable price.”

Maggie de Oliveira, International Admissions Advisor at Bridge agrees that being involved in these programs was an exciting opportunity for Bridge, saying, “I was encouraged to see such high levels of engagement by teachers (…) I’m looking forward to future initiatives Bridge will participate in to further support the global English teacher.

“It was great to see our capabilities as an institution to provide the trainees with a quality online training program for their entire cohort. It took a lot of teamwork with our web developers, tutors, and administration to make sure we provided the trainees with a positive experience and supported their success in the short timeframe they had to complete the course, so I’m once again impressed and proud of our Bridge team that came together to make it happen,” de Oliveira says, adding that Bridge’s partner institutions also played a key role in helping to get this program launched. “I think it goes to show that there are a lot of institutions that are making strides in supporting their teachers’ success, and that is an important move to empowering the teachers themselves.”

Overall, more than 200 teachers in Mexico and Nicaragua have enrolled in TEFL/TESOL courses with Bridge. Depending on the specific teacher development initiative, teachers had between four and six weeks to complete the online course due to deadlines imposed by the respective governments.

Bridge tutor Karina Zew, who trained some of the cohort of students included in these programs, said they “showed great dedication and interest, resulting in assignments that reflected the teachers’ great passion in the field.” Many of the students were particularly engaged in their course despite their other professional and family commitments. “One that stood out to me was a woman who had recently become a mom. Her daughter was three months old and she was taking the course while changing diapers and putting her baby to bed,” Zew said. “Such courage and willingness amazed me!”

Mexico’s COPEI offers EFL teachers Bridge’s 60-hour Teaching Young Learners Certificate

English teachers’ association COPEI (Colegio de Profesionales en la Enseñanza del Inglés) is a non-profit organization recognized by the Mexican Ministry of Education, and its main responsibility is to help improve the quality and training of English teachers in Mexico. COPEI partnered with both Bridge and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) to provide EFL training to public school English teachers in the state of Puebla as part of Mexico’s National English Program (Programa Nacional de Inglés – PRONI).

PRONI is a yearly program that is implemented across every state in Mexico and led by the Ministry of Education. Its main aim is to ensure the quality of English language teaching and learning in public schools in Mexico. Through PRONI, students in primary and secondary schools are given the opportunity to learn English as a second language, and teachers are provided with training to improve their language and teaching skills.

“English teachers were not provided with training opportunities in the past,” Ismael Garrido, the President of COPEI, told BridgeUniverse. “We have to recognize, though, that [through PRONI] the Mexican government has tried to improve the teaching of English in Mexico,” he added.

After searching for an online course that suited its needs, COPEI selected Bridge’s 60-Hour Specialized Certificate in Teaching English to Young Learners to train 56 English teachers in Puebla. “We liked Bridge because they offer a comprehensive specialized course for teaching English to young learners,” Ismael Garrido explained.

“We enrolled 56 teachers currently teaching in public schools in Puebla, Mexico,” Ismael Garrido said. “They had a month to finish the training course and they did a good job and deserved the certificate granted by Bridge.”

Bridge and Mexico’s GLCC partner to provide 100 teachers with the 120-Hour Master Certificate

In 2020, GLCC (Global Learning Consulting Canada), an educational consulting company based in Mexico, partnered with Bridge to win a federal bid to provide teachers and students from Estado de México, which includes the capital, Mexico City, with training and certification in general English, including methodology for teachers, such as TEFL/TESOL training, as part of Mexico’s national PRONI English program.

GLCC, which works with schools and governments to provide training and professional development to all kinds of teachers across the country, reached out to Bridge at the end of 2020 to discuss partnering to offer 100 Mexican EFL teachers access to Bridge’s 120-Hour Master Certificate.

“Given Bridge’s reputation and the kind of products [offered] and the international projects it has participated in, we decided to give one of its many training courses and certifications an opportunity, and with excellent results,” said GLCC’s General Director, Adriana Oviedo, explaining why the company chose to work with Bridge.

The Mexican government is focused on increasing the English language skills of Mexican students to improve their future employment prospects and because of an overall deficit of English teachers, is focused not only on boosting the skills of teachers coming into service but also on improving the skills of current English teachers in public schools. As part of this wider effort, for this project GLCC partnered with the Ministry of Education in Mexico City to offer broad-ranging TEFL/TESOL certification to English teachers working in local public schools.

“GLCC can offer teachers the best educational solutions on the market and we have the best products and most qualified staff. GLCC’s commitment is not only to teachers but to anyone who wants to learn English,” Adriana Oviedo told BridgeUniverse. “The yearly program offered by the Mexican Ministry of Education has not always offered the best quality in products, services, courses, and certifications. Because GLCC presented a new product within this program and we have had such good results in the past, the demand to keep working with us has increased.”

Adriana Oviedo noted that implementation of the certification project had seen some challenges, namely timing issues, “because there are some government projects in which timeframes are not ideal and we need to adjust them depending on the specific needs of the area we are working in, and the contracting entity.” She added, however, “given Bridge’s flexibility, we had the opportunity to finish on time. Bridge’s staff was also very attentive to immediately solving technical and commercial issues and its whole approach and support to us helped us solve issues quickly.”

Universidad Americana (UAM) in Nicaragua trains 67 teachers through Bridge’s Educator Plus course

In Nicaragua, Bridge has partnered with Universidad Americana (UAM) to provide public school English teachers access to Bridge’s 100-Hour Educator Plus professional certificate course.

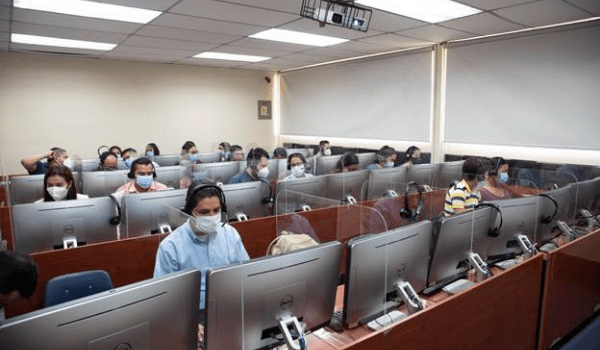

UAM’s project was part of a wider initiative by the Nicaraguan government and funded by the World Bank through the CARCIP (Caribbean Regional Communications Infrastructure Program), which in turn is a project run by Nicaragua’s Institute of Telecommunications and Correspondence (TELCOR). The wider project is intended to strengthen human digital talent and innovation in the region, and improve English skills both for training and to allow more adults to be employed in the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry. The ultimate goal is to reduce poverty in emerging economies.

The World Bank/CARCIP/TELCOR project has awarded 1,747 scholarships in English skills training as well as 910 scholarships in soft skills, and 52 scholarships in IT skills. To certify what the teachers had already learned through this program, UAM sought out a TEFL/TESOL certification course to offer to English teachers with a current English level of B1 or above, according to the Common European Reference Framework for Languages.

“UAM initially had another solution for their teachers in mind,” explains Johnson, “but it fell through. So, they found themselves looking quickly for a teacher training program of quality that would benefit their groups of Nicaraguan teachers. They reached out to us, and we quickly provided them a viable solution for this group.”

According to Hope García, Academic Coordinator of the UAM Language Center, “Nicaragua is in permanent need of educational support. One of the major goals of the government is to increase the quality and skills of English teachers to provide teachers with the latest trends in teaching and development. By providing teachers with these qualifications, they will be able to make a life-changing impact on their students.”

To measure the impact of the programs, the Nicaraguan government has developed a follow-up system to track the teachers’ performance. The system consists of scheduled visits to document the teachers’ new strategies and review the effect on the learning outcomes.

Combined approaches of specific countries suggest a route to success

According to the 2017 Inter-American Dialogue report, “half of the public schools in Mexico City have English teachers, but less than 10% of public schools in other, poorer, states, (…) have English teachers. Estimates project a need for 80,000 additional English teachers to offer universal instruction across the country.”

In Costa Rica, figures for 2014 show that of all primary school teaching positions that were not filled that year, 95% were positions for English teachers.

These figures suggest that the demand for English teacher training will only increase in the future, both in Mexico and in Latin America as a whole, and online courses, such as those offered by Bridge, may be a cost-effective way of providing that training.

While the Inter-American Dialogue 2019 report did not cover the countries in which Bridge has had partnerships – it focused on Chile, Costa Rica, Panama, and Uruguay – it does offer up insights into some of the approaches taken in the region for training English language teachers and what it takes for these government programs to be successful.

Sarah Stanton with the Inter-American Dialogue Policy Center tells BridgeUniverse that the research behind their report found that an initial assessment of language proficiency of English teachers already working in public schools was one effective approach to deciding which teachers might benefit most from professional development training. This is also a way of ensuring that the cost-to-benefit ratio is kept as high as possible in countries that are often faced with budgetary restrictions, which may now increase in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences.

Costa Rica, for example, carried out a prior needs assessment of practicing teachers in 2008 and then used the information gathered to target the teachers that would benefit most from additional training. According to the Inter-American Dialogue’s report, “it offered additional training and education to those teachers who failed to meet the established proficiency standard.” When the Costa Rica Ministry of Education then retested teachers’ language abilities, “there was a marked improvement in English teachers’ English proficiency levels.”

Chile’s National English Program, English Opens Doors (Inglés Abre Puertas – PIAP) was founded in 2004 and is regarded to be Latin America’s longest-established national English program. PIAP leads professional development programs for teachers including online courses, teaching workshops, teaching opportunities at English camps, and scholarships to study at English-speaking universities for a semester. The semester abroad is an incentive for teachers to improve their English proficiency and teaching methodologies and offered only to a select number of teachers who make the grade.

Using a more blanket approach, Panama adopted a program called Bilingual Panama (Panama Bilingüe) in 2014 with the ambitious target of making the entire population bilingual in English and Spanish. One aspect of this program was intended to increase the English proficiency of some 25,000 Panamanian EFL teachers working in public schools, at high speed. The country sent large numbers of these teachers on eight-week intensive English language programs to some 30 partner universities in English-speaking countries, including in the UK, the US, Australia, and the Caribbean. However, Panama scrapped the initiative in 2018, as the costs were too high for the benefits gained in terms of improvement of teacher quality.

Increasing English proficiency and teaching skills of EFL teachers in Latin America obviously requires a more cost-effective approach. Access to online training, such as that offered by Bridge, is a less expensive solution that can reach a higher number of teachers for a smaller cost. However, this approach has limitations in a region where Internet access is patchy at best.

“Across Latin America, the main barrier to online programs is connectivity. Many countries don’t have adequate levels of connectivity in schools all over the country. Also, access to the Internet is highly tied to socioeconomic status,” Stanton said.

In terms of approaches to increasing connectivity in the region, Uruguay provides the best example as, “they already they have the highest connectivity rates in Latin America. When broadband was installed, there was a partnership with the national utility provider to ensure broadband was installed in schools along with the power grid. This secured Internet access in basically every single school in the country. So, there is 100% coverage functionally,” Stanton explained.

Uruguay’s Ceibal en Inglés program, in which English is taught to students via videoconferencing, was developed to make use of the country’s high levels of connectivity in order to address its lack of qualified English teachers. According to the Inter-American Dialogue, Uruguay uses videoconferencing both to provide English classes to students as well as teacher training.

Whatever the approach taken in each country, it is worth noting that despite economic and structural limitations to providing training for English language teachers in Latin America, demand for quality teachers across the region will continue to grow. As Internet connectivity increases, particularly driven by the challenges and disparities placed on the region’s educational systems on the back of the COVID-19 pandemic, using online resources for both EFL teaching and training will continue to be a growing trend.