If you have long passages, DeepL does come up with language that is more natural overall. But DeepL often mistranslates words and shorter phrases.

When Google Translate first launched in 2006, the implications for foreign language classrooms seemed small. It was useful for translating single words, the way a bilingual dictionary is, and short sentences or phrases, but not accurate enough to translate longer passages into natural-sounding language. Google Translate relied on statistical machine translation, in other words, data from bilingual corpora rather than grammatical rules. For the most part, foreign language teachers ignored it or perhaps demonstrated to a class how it wasn’t very accurate by translating a paragraph from one language to another and back again.

Over time, Google Translate added features such as iOS and Android apps, but it wasn’t until 2016 that the very nature of its translation changed to neural machine translation, a system that uses an artificial neural network and produces much better results for longer strings of written words.

Not quite a year later, DeepL, named for the “deep learning” provided by neural machine translation, launched their own service. Developed by the German online translation company Linguee GmbH, which uses bilingual concordances or corpus-based contexts, DeepL now offers both a free, web-based service and a paid subscription.

With the superior translations provided by neural machine translation, it is time to take another look at their implications for the language learning industry and the classroom. While there do exist sophisticated paid machine translation tools, since learners most heavily use the free tools, this article limits itself to the most popular of these free services.

How Good Are Machine Translation Tools?

If you were translating a menu or an informational brochure, MT would serve better results than it would for literature … but if you were seeking a novel to read in translation, you’d want one that had been translated by a human.

“Are the translations provided accurate?”

This is the first question to ask. If students learning English were asked to write an essay, would they get similar or better results by writing first in their native language (their L1) and then having it translated into English (their L2, or second language) than they would by writing it in English themselves?

When I asked Patrick Conaway, associate professor of English at Shokei Gakuin University in Japan, what type of machine translations, or MT, his students use, he said that there is a clear difference.

“Well, I can tell if they’re using Google Translate, but if they’re using DeepL, I can’t tell,” Conaway said.

He explained that it’s not that a DeepL translation is entirely flawless, but rather that it produces grammatical writing that a high- or intermediate-level student would produce.

Sometimes students are caught turning in an entirely translated essay if they simply cut and pasted from DeepL and didn’t go over the results first. Instructors may think they are reading an original essay until at the very end they find “Translated with www.DeepL.com /Translator (free version).” Additionally, DeepL will sometimes offer variations of the same sentence, among which the user is meant to choose. A student who didn’t read the resulting translation and didn’t notice these choices would leave them all in and tip off the instructor that the essay had been machine translated.

Not everyone agrees that DeepL is the gold standard for translating longer language strings. In a Facebook group devoted to online learning, Samantha Kawakami, a part-time university English teacher and owner of a private language school expressed her skepticism of the program.

“A lot of teachers (myself included) have been talking about how much better DeepL is than the other translation software out there,” Kawakami said. “But the more that I use it, I do not think it is actually better. If you have long passages, DeepL does come up with language that is more natural overall. But DeepL often mistranslates words and shorter phrases. Google Translate and Bing Translate both seem to do better with individual words and short phrases. On a couple of occasions, DeepL has also ignored whole sentences and left them out in the translation. I have not had either Google or Bing make this particular error.”

Kawakami also underscored the importance of checking any translation.

“[Machine translation] can be used to get and to convey general meaning,” she said. “But the software does not produce language that can be used as-is. Using translation software can make things easier, but we need to carefully look at the translation and make sure it is correct. So, a certain level of language ability is needed to gauge the accuracy of the translation. Translation software has gotten better but it still has a long way to go.”

José Domingo Cruz, an English instructor at Kyushu Institute of Technology, notes that one advantage Google Translate has over DeepL is more useful pronunciation information, and more useful links to click for further study.

“DeepL kicks when you need an entire letter fully translated,” Cruz said.

Both DeepL and Google Translate do better with what John McRae, past professor of Language in Literature Studies at the University of Nottingham, calls referential language, as opposed to representational language. Referential language is largely transactional. Information is requested or presented, and meanings are literal. Representational language, on the other hand, engages the imagination and makes use of figurative language.

“Where referential language informs, representational language involves,” McRae said.

If you were translating a menu or an informational brochure, MT would serve better results than it would for literature. This is one reason the translations you see on websites as you surf the internet are generally entirely adequate to communicate the information there, but if you were seeking a novel to read in translation, you’d want one that had been translated by a human.

Is Machine Translation Ethical?

“Does students’ reliance on MT represent an absolute evil or might there be sound pedagogical uses for Google Translate?”

If a native speaker of another language were writing in English and didn’t know how to say one word, no teacher would be surprised if he or she used a bilingual dictionary. In fact, that would be expected. Using a dictionary while writing an essay at home is not only not considered cheating, but it’s considered a valid strategy. Textbooks and teachers explicitly teach dictionary skills like how students can make sure they’ve chosen the right definition, how to check for collocations and how to use the word in a sentence. Dropping one foreign word into Google Translate and getting the English equivalent doesn’t seem any different from checking a bilingual dictionary.

But that’s at the word level. If the same hypothetical language learner entered a complete sentence instead of an isolated word, would that be cheating? At that point, the student is receiving grammar and syntax and not just lexis.

How about if the student put in a whole paragraph? Or a whole essay? On this last point, teachers agree that it is not all right.

“If using MT is fine, then what’s the point of language learning or teaching?” asks Rachelle Meilleur of the Kyoto University of Foreign Studies.

It can be difficult to know where to draw the line. It depends too on how students use machine translations.

“I think there’s a big difference in using [MT] to understand text, and/or to see how your own work compares, to using it as an alternative to actually doing the work yourself,” Meilleur said. “The reality is that students are not using that way most teachers think they should. They just dump their translated text into DeepL and hand that in, maybe with a few corrections … I’ve had students who were so low they could not speak to me without using a dictionary, yet produced native speaker-like papers.”

Back in 2013, a survey at Duke University on faculty reactions to MT in foreign language classes found that more than two-thirds of those surveyed did not approve of students using machine translations. A majority did not feel that MT was useful for elementary-level students, although 30% felt it was somewhat useful for advanced students. MT was not felt to be any threat to language teachers or programs although that survey predated the advances in the accuracy of machine translation.

Even the title of a 2018 article by Ducar and Shocket, “Machine translation and the L2 classroom: Pedagogical solutions for making peace with Google translate,” reveals a bias against using MT. The authors discuss the “widespread yet generally unwelcome presence of MT in the classroom,” noting that “studies have repeatedly shown that L2 students consult the most widely used translation tool, Google Translate, in spite of the fact that its use is frowned upon by second language (L2) instructors.”

The article does try to find positive pedagogical applications for Google Translate, but the antipathy to it is still clear.

“Does students’ reliance on MT represent an absolute evil or might there be sound pedagogical uses for Google Translate?” the article asks. “Can, or should, we try to prevent our students from using this technology when, if we are completely honest, we turn to it ourselves in some situations? Love it (students) or hate it (instructors), the capabilities of MT will only continue to improve.”

Institutional policies have not entirely caught up with the issue. Most don’t address machine translation on their websites or in student handbooks at all, although they do explain plagiarism in general and outline disciplinary consequences. If machine translation constitutes plagiarism is often not mentioned.

Western Washington University, however, explicitly calls out “[s]ubmitting the results of a machine translation program as one’s own work” as a form of plagiarism.

The translation department at Boğaziçi University in Turkey does the same, including an example of plagiarism.

“Using machine translation tools (unedited or post-edited) with no declaration that such tools have been used [is plagiarism].”

The University of Chicago leaves it up to the instructor and the evolving landscape.

“With the internet, an integral part of academic research and the ubiquity of word processing methods, the opportunity to lift and reformat texts has greatly increased and ambiguity about the boundaries of legitimate collaboration has been introduced,” the school’s policies state. “It is advisable for faculty to discuss these issues in classes early in the quarter and to be explicit about acceptable practices on joint projects, problem sets and other collaborative efforts. One of the functions of teaching is to educate students in the norms and ethics of scholarly work, as well as in the substance of the field.”

Uses of MT in the Classroom

Chief among the objections to students using machine translation as language learners is that they won’t learn.

Chief among the objections to students using machine translation as language learners is that they won’t learn. As an analogy, a student using a calculator on a math test is using a tool, but Googling the answer to the problem and writing down the result would not be considered a demonstration of any skill (outside of Googling). Math teachers don’t introduce students to calculators before they have understood the principles of the basic functions. Writing a sentence in English and then checking a translation of a sentence from one’s L1 with MT is different from only producing the sentence in L1 and translating it. Most instructors assign writing texts in the language classroom to assess students’ ability to write in the target language. There may be an additional goal of, for example, assessing knowledge of a subject or critical thinking, but the formation of the target language is at least of equal, if not primary, importance.

Most teachers concerned about students translating as the first or only approach to language creation simply move those tasks from homework to in-class work. The switch to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic made that method more challenging, but it’s a favorite for in-person learning.

“When I was in classrooms, I prevented the problem by making them do all their writing in-class,” Cruz said. “Nothing to take home. The classroom prevents them from using any tools besides their pens and papers and dictionaries. If a student forgets their dictionary, they can ask me for permission to use their phone’s dictionary, after they disconnect it from the internet. Normally all of their writing is done in this way, including their final test. … That system has basically eliminated plagiarism in my classes for over a decade.”

If teachers don’t want students using machine translation, another solution is to make that a condition of the assignment and then react accordingly. Steve McCarty, a professor at Osaka Jogakuin University, follows this approach.

“A fundamental evaluation criterion for writing assignments has always been that it must be the student’s own composition,” McCarty said. “In the rubric, I add: ‘Not copied or translated.’ Having laid down the principle, I avoid being accusatory and just mark papers down according to the extent of the apparent inauthenticity. What disqualifies papers more often is not doing what was assigned, whereas translating might indicate that they at least thought about it. I should specify that this is for content-based EFL for English majors. Moreover, literacy supports speaking. The needs of students in general education English classes are different, but English majors who depend on auto-translation will not be able to communicate in real situations such as a job interview with an international organization.”

Other teachers use MT in class directly. Bryce Harris has used machine translation in his teaching with elementary, middle and high school students in Japan. He acknowledges that a primary challenge is “directing students to use it in the way that you, as the teacher, would like them to, in order to get the students to actually learn what you intend.”

But that rests with the structure of the assignment as well as the instructor’s skill and the learners’ approach.

One example Harris gives was in teaching a class of fifth-graders to write a recipe for curry and rice. Working in tandem with a Japanese teacher, Harris first had the children watch an instructional video in Japanese. Then the students wrote out the steps of the recipe, still in their L1. From there, they moved to English and wrote out the steps.

1) They wrote their ideas as accurately as they could, although they could consult a dictionary for individual words.

2) Then they entered their Japanese text into Google Translate and submitted that translation along with their own version to Harris.

3) Harris returned to the students a recipe that he wrote. He did not correct either their versions or the Google Translate version. The final step was to compare the Google Translate version with their own version and give an opinion, then compare the Google Translate version to Harris’ version and give an opinion. Finally, they compared their writing with Harris’.

So, students were learning more than English. They were learning how language works, how machine translation works and even how learning works. Harris wrapped up by asking students to suggest ways to use machine translation better, such as to use it for shorter sentences and language chunks where it is more likely to be accurate. This kind of learning about machine translation at the same time as learning the target language helps students to understand Harris’s views on the efficacy of MT, such as “[i]t’s always important to read the end result and to understand where it needs to be refined or totally ignored” and “[i]n order to produce your own work, it is important to be able to express your own thoughts in your own words.” Simply telling students those ideas is not nearly as effective as showing them.

“Machine translation is here to stay,” Susan Jones, professional translator, said. “So we had better learn to live with it, not fight it.”

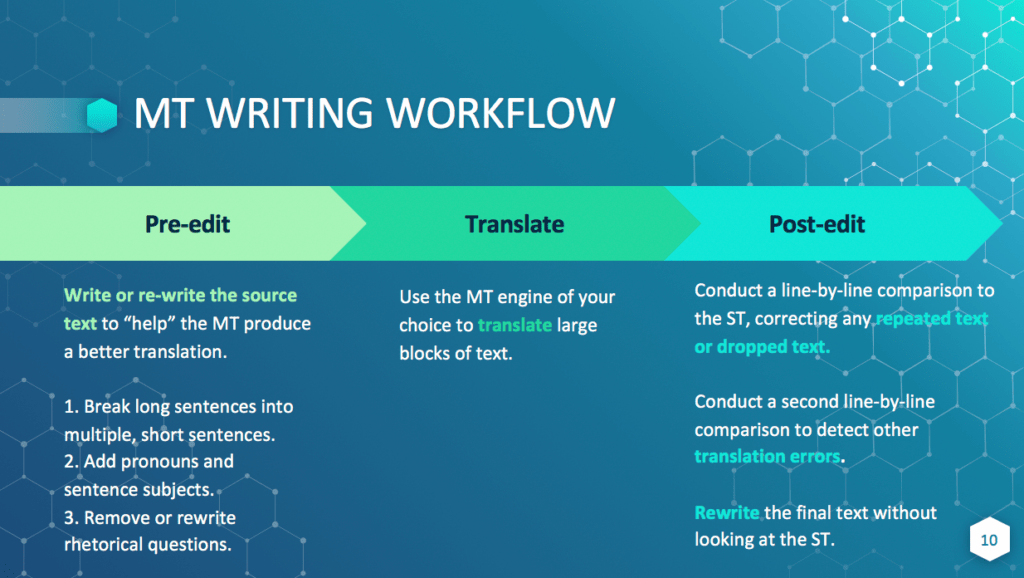

Rather than spending time trying to thwart students’ attempts to use MT or catch them having done so, Jones proposes teaching them how to use it more effectively. She takes her translation students through a carefully scaffolded process where they learn to prepare a document so that a program such as DeepL can do a better job of translating. They use the MT program of their choice, then analyze and improve the results by comparing the machine translation to the source text. Students who are taught how to use machine translation well have gained another tool to help their writing.

Monica Shinozaki, an English lecturer at Japan’s Oita University, wonders about pedagogical uses for instructors.

“One thing I struggle with is the accuracy of the students’ writing but giving feedback or correcting mistakes is mostly impossible in any classes of more than 10,” Shinozaki said. “Could DeepL be something that can help with that? To help students notice their mistakes and find better ways of expressing themselves. What about reading? I use DeepL mostly to help with my reading of Japanese. I first read and try my darnedest to understand a Japanese article before putting it in DeepL. Looking at the English translation immediately helps me understand the vocabulary and the grammatical patterns that I didn’t know before in the original article.”

Why couldn’t students use it in the same way?

Conaway uses DeepL himself for work.

“For me to deal with admin in Japanese … I could write my emails in Japanese, but it would take me an hour,” Conaway said. “So instead, I write my stuff in English, I put it in DeepL, and if it matches basically what I want it to say, I send it out as is.”

If a word isn’t accurate enough, he changes it, but usually it’s close enough, and often it is right on. He also uses DeepL for research, so he can read papers on topics of interest even if they’re written in another language.

“I’ve taken whole research papers in Japanese, on extensive reading, and dropped them into DeepL, and they came out readable,” Conaway said.

If teachers who are proficient L2 users employ DeepL in their own learning, it would make sense to help students learn to use MT in the same way.

Could Machine Translation Replace Language Teachers?

Google Translate isn’t going to make a foreign language department obsolete any more than dictionaries, phrasebooks and the existence of professional translators did.

One reason for some teachers’ distaste for machine translation could be a perceived threat to their careers. For a student who wants to become proficient in a foreign language, it seems clear that machine translation is only one of many tools to be used. Google Translate isn’t going to make a foreign language department obsolete any more than dictionaries, phrasebooks and the existence of professional translators did.

However, where machine translation might change the industry is in eliminating the incentive or the need for some people to take a short-term language class at all. If you were going to spend eight days on holiday in Australia and wanted to be able to read rental car booking information and hotels’ homepages and to understand a restaurant menu, knowing that you could do that from an app might eliminate the motivation to take a summer language course.

Academics who wish to read research in their discipline could use machine translation to access articles and websites. Even writing and publishing a subject-area paper in English could be done through machine translation with the added final step of employing a human proofreader. After all, native language writers use proofreaders for academic articles, novels and even correspondence, and nobody considers that cheating or disingenuous.

What Lies Ahead?

Both Google Translate and DeepL will continue to expand and improve. DeepL added Chinese and Japanese in 2020 and 13 additional European languages in 2021, bringing its total offerings to 24 languages. Notably missing are languages such as Arabic and Korean, but DeepL has promised to add more languages in the future, so surely those are coming, according to a recent article. As of August 2021, by comparison, Google Translate handled 109 languages, although not all at the same level.

In the language classroom, instructors need to clarify their own positions on how much MT use is acceptable and craft assignments that align with those expectations. Further, they are ideal people to introduce students to MT and explore its strengths and weaknesses. Even in non-language classrooms, instructors should be helping students understand how MT can help them access material in other languages, even if — in fact, especially if — they have no plans to learn those languages.

As MT grows, so will its usefulness to not only foreign language students but those who wish to read or write in a foreign language in a more limited way. Machine translation refocuses language learning and instruction rather than supplanting it. For those who truly wish to learn and engage with an additional language, machine translation is a useful tool to help understand equivalencies and differences among different tongues.