Freshta Noori was 11 years old when she started studying English in the fourth grade. She was 19 when she began teaching English while simultaneously working on her teaching certification. And then at age 20, the Taliban took over the governing of Afghanistan, and her world changed. Now she can no longer leave the house without a male escort, let alone go to school, either to learn or to teach.

In less than a month, the landscape of English teaching in Afghanistan changed. To understand what that change looks like, I spoke with a number of English teachers like Freshta, through email, Zoom and messaging apps, about their experiences. Some of those teachers have chosen to remain anonymous or to use a pseudonym out of concern for their safety. Not too surprisingly, I found teachers working in a variety of scenarios. There are different situations in different provinces and even among cities in the same province, and the situation there remains fluid.

What brought about the 2021 regime change?

The United States toppled the Taliban’s regime twenty years ago as a response to the September 11, 2001 bombings of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon; U.S. troops had been stationed on bases in Afghanistan ever since.

In 2020, then-President Donald Trump signed an agreement with the Taliban to begin withdrawing U.S. troops and lifting sanctions in exchange for assurances that, among other things, “The Taliban will not allow any of its members, other individuals or groups, including Al Qaeda, to use the soil of Afghanistan to threaten the security of the United States and its allies,” as the signed agreement stated.

Trump had originally promised U.S. troop withdrawal by the end of April 2021, but incoming President Joe Biden postponed that to coincide with the September 11 anniversary. Angry at the delay, the Taliban began capturing towns in northern Afghanistan, and as their power grew, they targeted larger cities. Kabul fell in mid-August, and the U.S. government rushed to remove their remaining personnel. With the capture of the capital, the Taliban’s hold over Afghanistan was nearly complete.

What did English teaching look like before the Taliban takeover?

“Teaching is considered a necessary and sacred thing in any society.”

In the last few decades, educational enrollment in general and the enrollment of girls, in particular, had been increasing, though poverty, a lack of qualified teachers and a lack of adequate facilities still presented challenges.

USAID (United States Agency for International Development) had also been working since 2008 to improve facilities and promote educational access, particularly for girls, and by 2020 they had provided nearly 11,500 two-year scholarships to women to attend teacher-training colleges. Between 2001 and 2020, the student population grew from 900,000 male students to over 9.5 million students, of whom 39% were girls.

Both boys and girls were able to study English in many public schools, usually from high school age. Both genders could continue studying English at university or in private language centers. The most common reasons to study English were for jobs or to pursue advanced study in another country. Both the British Council and the U.S. State Department carried out projects that promoted English language education, often through teacher-training initiatives.

Not all schools mixed the genders while studying — for example, the Afghan Opportunity Centers, established in 2017 to serve disadvantaged youth in rural areas, separated boys and girls into not only separate classrooms but separate buildings as well.

And why do so many wish to study English? “Because English is an international language and is spoken in most countries,” replied one English teacher. “Knowing English helps university students access first-hand information. I wanted to understand this language in addition to graduating in computer science, and this language would help me get a better job in Afghanistan.” Again and again, I heard a variation of those reasons — to get a job, or a better job; to study further; to connect with the rest of the world.

Those who had chosen to go into teaching spoke often of service. “Teaching is considered a necessary and sacred thing in any society,” explained a teacher from the provinces.

A teacher who has since left Afghanistan explained, “It was my dream to be an English teacher to serve a country which had no standard classes, sufficient schools, or adequate universities. I and many more youths like me tried their best to serve the country, but unfortunately, everything has been destroyed.”

What does English teaching look like now?

The current status of English teaching in Afghanistan is unclear. Many schools and centers have shuttered completely — at least temporarily, citing security concerns and general uncertainty. A few have reopened but with fewer students, and some without any female students at all.

“The Taliban won’t let us teach English”

Governmental universities are still closed all over the country, but even if they are allowed to reopen, who will teach there? “Many of our best professors have already left the country,” one teacher, who wished to remain anonymous, told me. “I had many plans for the future — I had plans for obtaining further certifications — but after this, all of them will disappear because the Taliban are against learning English. I recently got a job as an English teacher with (center name redacted), but everything has changed and come to an end because the Taliban are not allowing us to teach English anymore. I wish I could teach English for my people, but I will no longer be able to.” Another recently employed English teacher resigned from his position, even though his center was still open, because of security threats.

Some teachers have been warned that teaching English could be seen as “promoting Christianity” and is therefore forbidden. Other schools have been told that they will be allowed to open but haven’t received news about any firm dates, and they worry that permission could be withdrawn.

Nationally, girls may now only study up to the sixth grade. Some language centers have sent all their female teachers and students home, out of concern for their safety. Furthermore, if girls are allowed to study at all, it can only be with female teachers. But how do new female teachers become qualified if they themselves are not allowed to study?

A recent BBC broadcast from October 2021 highlighted the frustration and despair of girls whose education was abruptly ceased. Women took to the streets of Kabul to protest and were beaten and lashed with electrical wires. The female BBC reporter interviewed a Taliban leader who said that the Taliban is not preventing girls from going to school; rather, the Taliban is only waiting to open all-girls’ schools. Yet currently girls are still forbidden to attend secondary school. Whether new schools will be built for girls, of course, remains to be seen.

Open and shut and open again

“The object of our lives is to serve humanity, to teach them, to guide them. It is not a crime. If the Taliban came to my center, if they asked me, ‘Teach us,’ I’m sure I would teach them — because I’m a teacher.”

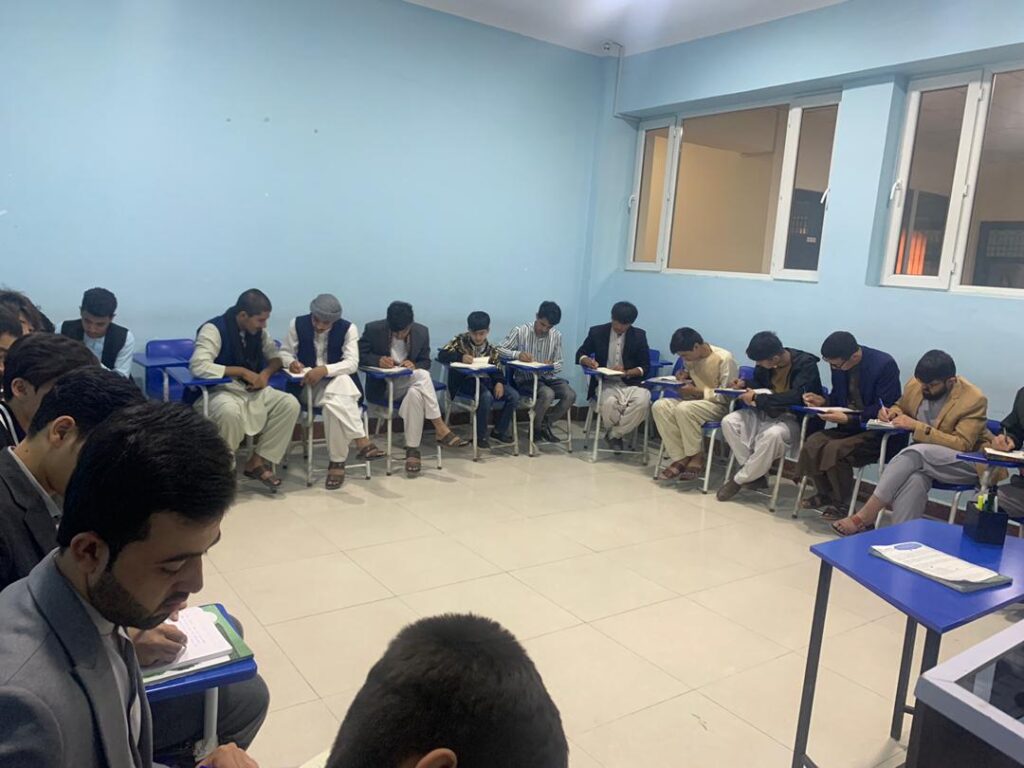

A CELTA-certified English instructor from an international training and testing center in Mazar-e-Sharif, who asked to remain anonymous, remains determined. His center, one of 23 adult learning centers throughout Afghanistan, was closed in August. Just the month before, in July 2021, they had nearly 2,000 students, both male and female teachers, and provided not only English language classes but computer courses and English teacher certification courses — 88 classes a day, six days a week. All of his teachers had master’s degrees and/or teaching licenses, but suddenly they had nowhere to go. He was particularly concerned about his female teachers. Would he be able to employ them again?

The teacher first met with the head of the Taliban’s education department in August, together with twelve of his teachers. He was told at that time that male teachers would not be allowed to have female students in class. However, he didn’t have enough certified female teachers on staff to cover all of the girls’ classes as some of his female staff had already managed to leave Afghanistan and relocate to other countries.

Clearly, the situation weighed heavily on him. “When we cast the lens back on our past, one or two months ago, and compare it with this situation … We have lost the simple values of happiness and satisfaction. Myself, the teachers, the staff, the female teachers … sometimes they call me. But no one knows what to do or where to go. It’s too hard.” He worried about his students. “We had good students, talented students. In our center, the students were university students, and some high school students — we had medical students, engineering students … nowadays, English is the key to science and technology. Some of them wanted to be politicians. Three days ago, some of the advanced students — most of them were female students — came to us and said, ‘We miss the center. Why won’t you open?’”

But the teacher persevered and met with the Taliban again in September. This time he got better news: The center could reopen and even teach girls, as long as male and female students studied in separate classes with same-sex teachers. He himself had first started teaching English when he was still a student, covering at his director’s request for an absent teacher. So, he’s taken a similarly innovative approach to the issue of not having enough certified female teachers: The organization he works for is offering an onsite 120-hour certification program for both male and female teachers, and he will let interested but uncertified female teachers work in teaching while studying at the same time.

The center has not rebounded to its July numbers yet. Currently, they have about 300 students, mostly male, though the numbers are gradually increasing. There are other changes too. Students are struggling with increased poverty, and many have requested tuition discounts. Many students and teachers alike report feeling insecure about attending classes as well as disappointed in their future prospects.

“I’ve taught thousands of people in Afghanistan and Pakistan. We are not doing anything wrong! The object of our lives is to serve humanity, to teach them, to guide them. It is not a crime. If the Taliban came to my center, if they asked me, ‘Teach us,’ I’m sure I would teach them — because I’m a teacher,” he says.

Moving online

Another teacher, who wished to remain anonymous, was teaching at the Kunar Opportunity Center, which used to serve over 2,500 underprivileged students. Like the other Opportunity Centers in different cities such as Helmand, Kandahar, Urozgan and Zabul, they are being managed by Shaukat Zamani, an Afghan entrepreneur and philanthropist currently based in New Zealand, who has set up the Afghan Nation Building Organization (ANBO). While the centers are still open and free of charge, a jump in poverty levels now means that some students cannot attend in person.

Partly to address these needs, he is now teaching online, also through the ANBO, using WhatsApp groups. But don’t imagine a chaotic chat; the instructors have a set schedule that follows an elaborately structured curriculum that covers vocabulary, grammar and other language points. The students have books or materials at home, and the teacher provides language input and elicits responses during the online lessons.

Ironically, WhatsApp provides a “classroom” in which boys and girls can study together, as they don’t see one another. Some of the girls also have male teachers, although Zamani has been recruiting female teachers for the girls as well.

Unable to travel to her former English center, where she taught both children and adults, Freshta Noori also turned to teaching online, through the app Hallo. However, because she wasn’t certified, she could only find volunteer teaching opportunities, which she spoke about with enthusiasm. “I’m teaching globally now — students come from all over.” She initially looked for students inside Afghanistan but didn’t find any, which she posits is due to a lack of widespread internet access. “Instead, my students are from India, Bangladesh, the Philippines and from so many other places.”

When I asked if the Taliban allowed women to teach online, she shrugged. “I don’t give my location. They won’t know.”

Are English teachers leaving Afghanistan?

While several teachers I spoke with mentioned, with some envy, teachers they knew who had emigrated, it’s neither simple nor easy. In order to secure a visa or permission to immigrate, people needed a connection — to have worked with a foreign organization, for instance. Many who had worked as informal or volunteer translators found that the lack of verifiable employment meant that no visas were forthcoming, and of course, many English teachers simply didn’t have any such connections. “I tried so hard to leave Afghanistan, but there was no way. I didn’t work with the Americans or any other foreign countries who could help me,” explained one teacher.

“I was a volunteer translator (for NATO and a team from New Zealand), and I got left behind,” added another teacher, not without some bitterness. “My life here in Afghanistan is not safe, and I ask each of you to help me get out of Afghanistan as my life is in extreme danger.”

One teacher who managed to leave is Abdul Hameed Mansoory. In addition to the teaching he did at private institutions in Baghlan province, he worked as an interpreter and translator for ISAF troops from the Hungarian army (the ISAF, or International Security Assistance Force, was a multinational military organization that served in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2014). The recipient of a scholarship to study in India through the U.S. Embassy, he wrote first to the Americans to ask for help in leaving the country. When the U.S. wouldn’t evacuate him, he turned to the Hungarians, who did. Mansoory is now living in a camp in Vámosszabadi, Hungary and is looking for work and hoping to connect with other English teachers in the country. His long-term dream is to pursue a Ph.D.

What can you do?

“But we still have hope. We go on. That’s what I love about my country — the courage. The people here are still working hard to make their voices heard. They’re not afraid of anything.”

It is beyond the scope of this article to recommend aid organizations. However, if you feel moved, I urge to you look for reputable organizations in your country or community and ask how you might help. If any Afghan refugees have been relocated to your community, they could almost certainly use some help with settling in — English language lessons, most likely, but also assistance with housing, schooling for themselves and their children, and finding work.

I asked the teachers I spoke to if they had anything they would like to tell the world about Afghanistan. Almost all of them expressed a wish for the international community to witness their situation and be aware of the challenges they’re facing. The teacher we spoke to at the training center in Mazar-e-Sharif said, “They should know about the achievements of the last 18 or 20 years. They should know about the talents of the Afghan people. They should know Afghanistan has progressed. We have the talent; we have the potential.”

“In my country, we were always embarrassed that nobody knows us,” says Freshta, with a smile. “We are the people that no one knows. But in spite of our background, what I see in my country, what I love, is the courage that my people have, even in this hard situation. Maybe people from other countries, if they were in this situation, they would try to leave; they would feel hopeless. But we still have hope. We go on. That’s what I love about my country — the courage. The people here are still working hard to make their voices heard. They’re not afraid of anything.”

Finally, from one anonymous teacher: “I sincerely urge the readers of this text to raise their voices because of the security situation in my country, and I call on the international community to help my people.”