The rising demand for English teachers worldwide has provided Filipinos with much-needed employment opportunities and significantly affected other ESL (English as a Second Language) industry stakeholders. Large corporations profit from the Philippines’ competitive labor rates and the high global demand for English language instructors. BridgeUniverse spoke with two Filipino English language teachers (ELTs) and the managing director of an online English language platform to find out how they rate their experience teaching in the Philippines, online, and abroad, whether they believe their pay is fair and how the rising trend of hiring teachers at lower rates is affecting the industry as a whole.

The Rising Demand for Filipino English Teachers

A 2012 article by BBC Business, titled “The Philippines: The world’s budget English teacher,” points out two key reasons overseas students choose to learn English in the Southeast Asian island nation: the low cost and the teachers’ accent. These overseas students, primarily from Iran, Libya, Brazil and Russia, benefit from high-quality language instruction while paying only about one-third of the price of English language courses in the U.S. or Canada. In addition, the teachers’ accent makes the Philippines a popular alternative to Western countries. From 1898 to 1946, the country was under American occupation and, consequently, English became an official language. As a result, depending on education level, Filipinos today speak with an American accent.

English proficiency levels in the country also led to a boom in the country’s $26.7 billion Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry, a top contributor to the Philippine economy, employing roughly 1.3 million people in 2019. The BPO industry involves foreign corporations that outsource jobs and even entire departments, including accounting, customer service or marketing to the Philippines, primarily for the low local labor rates.

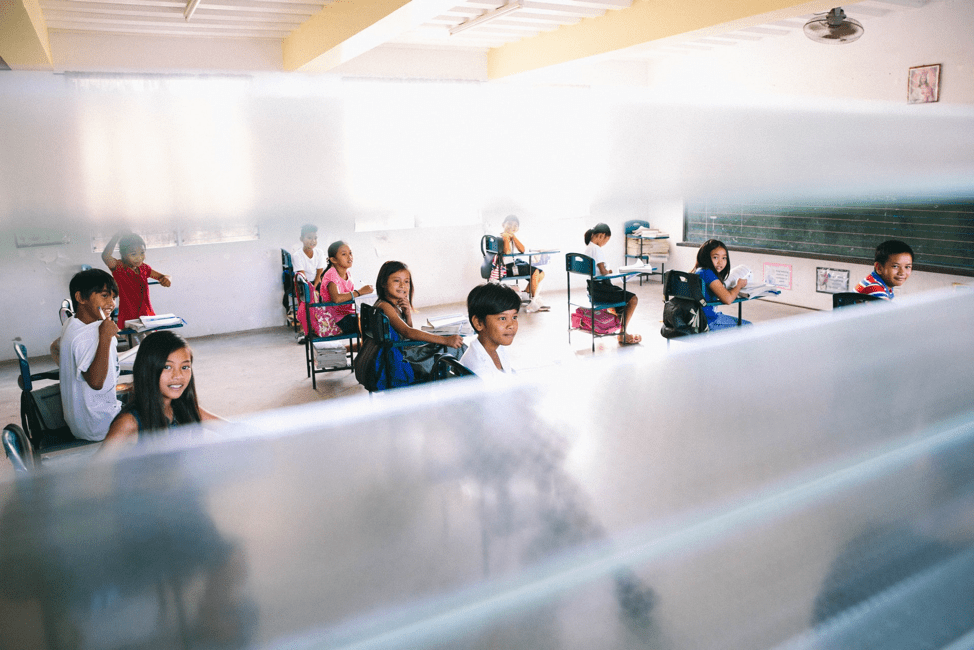

Due to the Philippines’ low average salaries across all job sectors, a significant number of its citizens move abroad for job opportunities with higher pay rates than they could earn at home. According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, about 2.2 million Filipinos worked abroad in 2019. These Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) work primarily in elementary occupations as service and sales workers and as plant and machine operators and assemblers. Many OFWs leave their families, including their children, behind and are separated from them for many years. In contrast, Filipinos who choose to venture into English language teaching can opt to teach online and stay at home.

Before China’s recent education crackdown, Chinese ESL company Acadsoc boldly promoted its salaries to prospective English teachers. “Teach more, earn more! Earn as much as 60,000 Php/month” (which is roughly $1,200 per month), the homepage of the website reads. In a country where, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority, the average yearly family income in 2018 was equivalent to $6,280 (about $515 per month), a stay-at-home job to teach English online promising more than twice the national average income is enticing.

Becoming an ELT in the Philippines

“I am quite proactive and regularly attend webinars, conferences and sign up to do online courses to always keep myself updated on what’s new in the ELT field.”

The process of starting a career as an ELT in the Philippines is straightforward. It requires searching the internet for an opening at one of the many language schools, sending in an application, completing the requirements, being interviewed and, once hired, obtaining a certification. Sometimes, these certifications, including TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) or TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language), can be earned while already working. For example, Jannelle Ruiz Gerong, a Filipino ELT based in the Philippines, had that opportunity: “The previous company I worked for offered us TESOL training, and I was able to finish the course while working.” When asked about English teaching opportunities in the country, Gerong says there is a steady, high demand. She explains, “tons of companies post job advertisements online. We can either submit our resumes online or in person. They hold interviews and tests before recruiting teachers. Some teachers are being trained for one month or less.” Gerong graduated from university in a different field, but — inspired by an acquaintance who worked as an ELT — eventually chose to shift careers and teach English. She was always interested in exploring English language teaching and applied to different companies to dip her toes into the industry as a fresh graduate. Today, she is TESOL-certified and has been an ELT for over three years, currently working for a small company in the Philippines.

A Filipino ELT living and working abroad is Karen Gacusan Deslorieux. She is a self-employed ELT now based in France. Deslorieux works in language schools and with private clients, teaching classes such as general English, English for tourism or marketing, and test preparation (e.g., for IELTS and Cambridge exams). For the past 12 years, she has been working in education, starting as a teacher’s assistant at the International School Manila and subsequently moving to Jakarta, Indonesia to work as a preschool teacher at another international school.

Upon returning to the Philippines, she married and, together with her husband, decided to move to France. At the time, her husband suggested she specialize in English teaching rather than early education for better employment opportunities in France. She says the decision to shift fields was worth it: “I landed my first job as an English teacher after six months of arriving in France. I am happy with the transition I have made in my career. I mostly work with French children ages 1 to 6. In a way, it’s like working with preschool-age children; the only difference is that I don’t have to teach all the subjects but just concentrate on teaching them English.”

Carlo C. Laroco is the head of BCM (Byung-Chul Min) Manila which is an online teaching and training center, primarily servicing students in Korea and Japan. When asked about whether continuing education for ELTs is provided at his school, Laroco explains that BCM is highly committed to the quality of the classes they provide to their students, which largely depends on the skills and wellbeing of their teachers. He adds, “For the people that we hire in our organization, it is a partnership. In fact, we conduct full-skill training, which includes communication, class handling, and soft skills. On top of that, we execute continuous developmental programs. We understand that the skill development of our teachers is imperative to achieve global success.”

Most English language centers in the Philippines, however, choose to train new hires for one month before they start to work, and then leave continuing education largely up to the teachers. Manila-based Nicolo Luccini began to teach English in China in 2009 and, in 2016, set up LearnTalk, an online English tutorial platform with mostly Filipino teachers. The marketplace model at LearnTalk provides teachers with initial training; however, continuing education and further professional development are left to the teachers independently. Deslorieux concurs, adding that continuing professional development (CPD) depends on each teacher individually. “I am quite proactive and regularly attend webinars, conferences and sign up to do online courses to always keep myself updated on what’s new in the ELT field.” Deslorieux adds that while TESOL and TEFL certifications are pretty standard in Asia, she noticed, after moving to Europe, that the CELTA (Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) was more widely recognized in European schools.

Teaching Online vs. Abroad

“When I was teaching English online back in the Philippines, I was paid around $5 per hour. In France, I get to charge more and base it on what the market rate is. For my services I charge from around 20-40 euros per hour. Needless to say, I prefer working in France because I am compensated fairly. Whereas in the Philippines, and working online from there, I need to be considered a native English teacher to earn at least $20 per hour.”

Up until recently, Chinese firms heavily recruited Filipino teachers for English online instruction, such as Beijing-based ESL giant, 51Talk, which in June of 2020 was still in search of 30,000 Filipino ELTs to hire — in addition to its existing 20,000 Filipino teachers — to alleviate the shortage of 500,000 foreign English language teachers in China. Luccini sees a clear benefit for Filipinos to teach English online rather than moving abroad to teach English in other countries: “It’s great because it keeps families intact. It’s more efficient and flexible.”

To Deslorieux, however, the major difference between teaching English online and moving to another country is the pay rate. She says, “When I was teaching English online back in the Philippines, I was paid around $5 per hour. In France, I get to charge more and base it on what the market rate is. For my services, I charge from around 20-40 euros per hour. Needless to say, I prefer working in France because I am compensated fairly. Whereas in the Philippines, and working online from there, I need to be considered a native English teacher to earn at least $20 per hour.” Gerong noticed another advantage of working abroad vs. online. “In my opinion, one advantage ELTs abroad have is that they have more control over the students and their classes,” she says. “Teaching English online can be quite difficult, especially with primary school students.” Aware that Filipino ELTs earn less than their Western counterparts while teaching online or in the Philippines, she adds, “another difference for me would be the salary.”

Wage Gaps

In the Bangkok Post article “Right qualifications, wrong colour skin,” Filipino ELT Lyndsay Cabildo recounts her surprise at the wage gaps for English teachers in Thailand. When she moved to Thailand in 2012, she was offered 15,000 baht (about $460) to work as a part-time English teacher in various schools around the country. However, for a white European teacher from a non-English speaking country, that price would be doubled, to 30,000 baht. She says, “Our salary was dictated by our skin color and not our ability to deliver or the credentials we worked so hard for.” The article goes on to explain that her experience is common for thousands of Filipinos seeking work in Thailand who often face discrimination based on race.

Due to the wage gaps Deslorieux experienced while teaching online from the Philippines, she prefers to work in France. In the Philippines, she was paid one-fourth of what her Western coworkers made for being considered a non-native English-speaking teacher (NNEST). “Here in France, I earn above minimum wage. Minimum wage in France is around 1,540 euros per month. I know that my Western counterparts are paid the same rate as me. This is what I really like about working in France — there is equality! I am paid not based on my passport but on my experience, degree, certifications and competencies.”

Citizenship and Race

“My students and employers in Indonesia didn’t treat me differently because I was not Western.”

The issues of native speakerism and race discrimination are widely debated in the ESL sphere worldwide, yet Deslorieux says she has only had a few related experiences. She says, “I think my citizenship, race and class didn’t matter with the jobs that I’ve had, except when it was online work. When I applied for online jobs, some companies declined me because I was not from a country considered as native-English-speaking.” While working as a preschool teacher in Indonesia, Deslorieux felt she was treated well by employers and students. “My students and employers in Indonesia didn’t treat me differently because I was not Western. I think that generally, Filipino teachers are regarded highly in Indonesia. Employers and the families we work with respect and admire our work ethic and dedication to our jobs, so it is prevalent to find many Filipino teachers employed in international schools in Indonesia.” When asked, Gerong says she also found that students generally gave Filipino ELTs good reviews. “Some of my previous Asian students told me they relate more to their Filipino teachers and that they like the way we speak and enunciate words,” she recounts.

“Racism is real. Yes, we all know this fact. Rarely does the pay level of a Filipino come close to that of a native speaker.”

In the article “Discrimination against Filipinos,” an Australian ELT based in Thailand shares a contrasting story, describing his observations of Filipino coworkers and their experience of working in Thailand. He writes, “Racism is real. Yes, we all know this fact. Rarely does the pay level of a Filipino come close to that of a native speaker,” noting that Filipinos are the lowest-paid English teachers in the school aside from the English-teaching Thai staff. The article “They Are ‘Asians Just Like Us’: Filipino Teachers, Colonial Aesthetics and English Language Education in Thailand” also examines the discrimination Filipino ELTs working in Thailand face. It describes how they “find themselves in a relatively disadvantaged position compared to their white, English-speaking coworkers,” being paid about half of what their native English-speaking (NEST) coworkers make and “enjoying less favorable housing arrangements and working conditions.” The article goes on to explain that the treatment of Filipinos as “second-class, English-speaking teachers” in some Thai schools is embedded in the colonial view toward the English language — as English is perceived to be interconnected with whiteness, white NESTs are therefore considered ideal English teachers, while non-white teachers face discrimination. According to the article, racial background is favored over English proficiency, again pointing to the issue of native speakerism. Both articles mention that Filipino teachers in Thailand were primarily female and expected to wear uniforms identical to those of Thai staff, while native speakers enjoyed a separate dress code.

The Future for Filipino ELTs

While China may not currently be an option for Filipino ELTs seeking to work abroad, many other countries are viable alternatives.

On July 24, 2021, Chinese state media announced a new policy that considers companies making a profit from after-school tuition services for school-age children illegal. Although mainly aimed at academic test-preparation schools, the new policy also covers language schools and online providers. In addition, providers are banned from being listed on any stock market and from teaching on weekends and during public or school holidays.

While China may not currently be an option for Filipino ELTs seeking to work abroad, many other countries are viable alternatives. In an April 2020 article, Philippine higher learning institute Enderun published a list of recommended countries to teach English abroad for Filipino ESL teachers. Topping the list were Japan and the United Arab Emirates, followed by Thailand and Spain.

Working abroad is one of Gerong’s plans for the future. “I enjoy being an ELT and am planning on obtaining more English-teaching certificates,” she says. “I would also like to continue teaching English abroad.” Already based abroad, Deslorieux says her ESL teaching future entails obtaining more certifications and focusing on adult English and niche teaching. “Since I am in France, I am thinking of specializing in teaching English to professionals in the wine, spirits and cheese industry,” she explains.

English language teaching has undoubtedly provided safe careers and stable incomes for thousands of Filipinos in the country and abroad for many years. Still, there seems to be room for improvement in the industry. “I hope Filipino teachers can get better pay, especially the ones working online,” Deslorieux says. She continues: “As for the teachers working abroad, it is important to know what the market rate is of the country where you are working. We should not undervalue ourselves just because of our nationality. If we have the experience and the competence, we owe it to ourselves to get decent pay.” Luccini adds, “It would be nice if some markets were less concerned with their teachers’ ethnicity and more concerned with the quality of their instruction. Unfortunately, some markets view ethnicity as a signal of ‘quality’ education, which is objectively incorrect. I hope this changes one day.”